At the end of the 20th century objects feel like heavier, more cumbersome and older. An illusory weight certainly, which can probably be justified with the dematerialisation of the goods or the general feeling of shakiness pervading the contemporary world, nevertheless decisive for understanding developments in recent sculpture.

The exhibition Unmonumental. The object in the 21st century, curated by R. Flood, L. Hauptmann and M. Gioni for the New Museum of New York City in 2008 has shown how recently all closed and assertive form has left room for different tentative premises, which substitute the precarity of the ordinary for monumentality.

For the choice of materials and the way they are involved, the research of Albert Coers reflects clearly these problems and takes position in the very centre of the actual sculptural production.

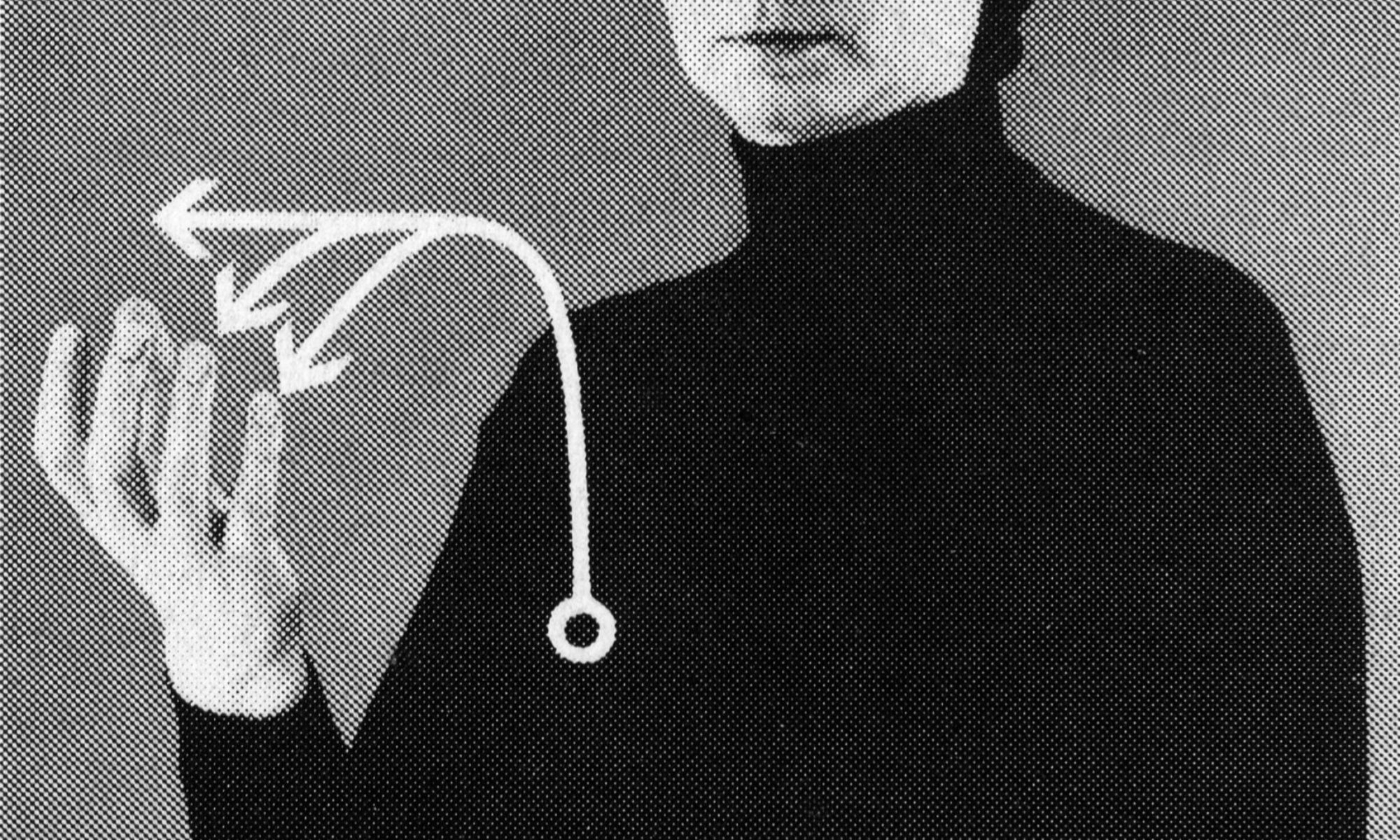

At the base of his work, there is a dialectic tension between monumental and ephemeral, which can be seen in the way in which the works are created. In the first moment, Coers chooses objects conserved in an context, which is accessible, but separated from the spaces of life, like a depository or a library, he exhibits them in a manner that denotes the objects as works of art and after the end of the exhibition, he brings them back in the context from which they came from. The ephemeral character of the work – a temporary rearrangement of reality – is defined by the sequence of actions, aimed to create temporary monumental structures of which remains only the photographic documentation. In this sense a paradigmatic example is Trasloco (2003), an installation, in which the boxes intended for moving the objects of a building form the model of the building itself. Collezione accademica IV (sgombero), where different objects are ordered in a room before the clearing out, makes evident how the relocation itself takes a sculptural significance in Coers work, which was already shown in a historic action by Allan Kaprow, but here he aimed to create a precise reflection upon the nature of materials. Even if in the research of Coers the use of the ordinary object is close to the way in which Shinique Smith (1972) ties up things in bales or Florian Slotawa (1972) transports furniture from home into gallery, works like Collezione privata (Sammlung – Sichtung – Schichtung) (2002) or the series Collezione accademica (2003–2004) show the attention of the artist for the spiritual component of the used objects, pieces of an archive of experience, revealed and celebrated in the moment in which they are exposed.

The contrast between the cultural weight of the things and their physical presence, which is already present in these works, manifests itself in the following, nearly exclusive use of books, often taken from his own library. In these works to the polarity of monumental and ephemeral, comes the presence of material and immaterial: the quality of volumes in terms of weight, dimensions, colour, interferes with their cultural value as documents. In the passage from document to monument, what transforms the books into works of art is their architecture: the volumes become bricks to form walls, columns, round arches, domes. Apart from the iconographic references, certainly not incidental considering the humanistic formation of Coers, the plastic quality in these works lays above all in the action itself of putting things in order, a process that inserts the work of the artist in a sculptural tradition exemplified first by Tony Cragg. Grids like the one that forms Collezione accademica III (2003) take on concreteness in the use of card-index boxes and bookcases that are able to exhibit to the visitor the related objects, in a function that makes them familiar to showcases. .

From both a static and structural viewpoint, the architectures of Coers are based on gravity, a fundamental sculptural element that assumes also a metaphoric value. The practice of stratification reflects the accumulation of history, page for page, but also that of books in a library, which are disposed and inlaid for filling up every available space, like stones in a dry stone wall.

The importance of the time factor shapes the space in the act of accumulating and fuses the process of creating intended as production of form (bilden) with the construction of a cultural education (Bildung). The interaction between form and content that is thus derived brings back once again the contrast between physical presence and spiritual value of the objects. And this is the semantic core of the work of Coers, where the duration of the cultural education of an individual — her of his life itself reflected by the collection — are celebrated in the moment of vision through a temporary merger of public and private actualized by the show.

Again, the beauty of the work is the result of the collision of immaterial and material, while its value is defined by shakiness, so much that also the moment of collapse can become a finished work in the form of ruins.

Massimo Palazzi, born in 1969. Artist and writer, currently based in Genoa (Italy), where he works as International Baccalaureate Art Teacher. After the graduation in Contemporary Art History he was admitted to the Haim Steinback’s Visual Art Advanced Course. His critical writing has appeared in Flash Art, Juliet Art magazine, Il giornale dell’arte. As curator he organized the exhibitions Eva Ultima (Novi Ligure, Italy, 2006) and Cold Frame (Genoa, Italy, 2004).

Il peso della cultura

E’ come se alla fine del XX secolo gli oggetti fossero diventati più pesanti, ingombranti e vecchi. Una gravità illusoria certo, giustificabile forse con la smaterializzazione dei beni di consumo o con la generale sensazione di precarietà che pervade il mondo contemporaneo, eppure determinante per capire gli sviluppi della scultura più recente.

La mostra Unmonumental. The object in the 21st century, curata da R. Flood, L. Hauptmann e M. Gioni per il New Museum di New York City nel 2008, ha evidenziato come ultimamente ogni forma conchiusa e assertiva abbia lasciato spazio a diversi assunti provvisori che sostituiscono la precarietà del quotidiano alla monumentalità. Per la scelta dei materiali e la modalità con cui vengono impiegati, la ricerca di Albert Coers riflette chiaramente tali problematiche e si colloca nel pieno della produzione plastica attuale. Alla base del suo lavoro, c’è una tensione dialettica tra monumentale ed effimero che si riconosce nel modo stesso in cui le opere vengono create. In un primo momento, Coers sceglie degli oggetti conservati in un contesto accessibile ma separato dagli spazi della vita, come un deposito o una biblioteca; li espone secondo una disposizione che connota gli oggetti come opera d’arte; al termine della mostra, li riporta al contesto di provenienza. Il carattere effimero dell’opera — una provvisoria risistemazione della realtà — è definito dalla sequenza di azioni, finalizzate a creare temporanee strutture monumentali di cui rimane solo la documentazione fotografica. In questo senso un esempio paradigmatico è Trasloco (2003), installazione in cui le scatole destinate a traslocare gli oggetti da un edificio formano il modello del medesimo edificio. Collezione accademica IV (sgombero), dove oggetti diversi sono ordinati nella stanza prima dello sgombero di uno spazio, esplicita del resto come il trasloco stesso assuma nell’opera di Coers una valenza plastica, già evidenziata da una storica azione di Allan Kaprow, ma qui finalizzata a una precisa riflessione sulla natura dei materiali. Benché nella ricerca di Coers l’impiego dell’oggetto quotidiano sia affine al modo in cui Shinique Smith (1972) lega in balle le cose o Florian Slotawa (1972) trasporta gli arredi da casa in galleria, opere come Collezione privata (Sammlung – Sichtung – Schichtung) (2002) e la serie Collezione accademica (2003–2004) evidenziano l’attenzione dell’artista per la componente spirituale degli oggetti utilizzati, pezzi di un archivio di esperienze, rivelate e celebrate nel momento in cui vengono esposte. Il contrasto tra il peso culturale delle cose e la loro fisica presenza, già presente in questi lavori, si manifesta nel successivo impiego quasi esclusivo di libri, spesso presi dalla propria biblioteca. In queste opere, alle polarità di monumentale ed effimero si sovrappone la compresenza di materiale e immateriale: la qualità dei volumi in termini di peso, dimensioni, colore, interagisce con il loro valore culturale in quanto documenti. Nel passaggio da documento a monumento, ciò che trasforma i libri in opera d’arte è la loro architettura: i volumi diventano mattoni per formare muri, colonne, archi a tutto sesto, cupole. Al di là dei riferimenti iconografici, non certo casuali vista la cultura umanista di Coers, il valore plastico di queste opere sta innanzitutto nell’azione stessa di ordinare le cose, processualità che inserisce il lavoro dell’artista in una tradizione di pratica scultorea esemplificata dal primo Tony Cragg. Griglie come quella che informa Collezione accademica III (2003) assumono concretezza nell’uso di classificatori e scaffalature in grado di esporre agli sguardi del visitatore gli oggetti rivelati, con una funzione che li accomuna alle vetrine.

Da un punto di vista statico e strutturale, le architetture di Coers sono basate sulla gravità, componente plastica fondamentale che assume qui anche un valore metaforico. La pratica della stratificazione riflette l’accumularsi della storia, pagina su pagina, ma anche dei libri in una biblioteca, disposti a intarsio per riempire ogni spazio disponibile, come sassi nei muri a secco.

L’importanza del fattore temporale condiziona lo spazio nell’atto di accumulare e confonde il processo di creazione inteso come produzione di forma (bilden) con la costruzione di una formazione culturale (Bildung). L’interazione tra forma e contenuto che ne scaturisce riporta ancora una volta al contrasto tra presenza fisica e valore spirituale delle cose. E’ questo il nucleo semantico del lavoro di Coers, dove la durata della formazione culturale di un individuo, forse la vita stessa che ogni collezione rispecchia, vengono celebrate nell’istante della visione attraverso una momentanea commistione di pubblico e privato che si realizza in occasione della mostra.

Ancora una volta, la bellezza dell’opera è il risultato dello scontro tra immateriale e materiale, mentre il suo valore è definito dalla precarietà, tanto che perfino l’istante del crollo può diventare opera compiuta in forma di macerie.

Massimo Palazzi, geb. 1969. Künstler und Autor, lebt z. Zt. in Genua. Dort Dozent für Kunstgeschichte an der International School. Nach seinem Abschluß in Zeitgenössischer Kunstgeschichte Zulassung zu Haim Steinbacks Visual Art Advanced Course. Artikel in Flash Art, Juliet Art magazine, Il giornale dell’arte. Kurator der Ausstellung Eva Ultima (Novi Ligure, 2006) and Cold Frame (Genua, 2004).