Es war ein ziemlich skrupelloses Unternehmen: sobald ein fremdes Schiff im Hafen der ägyptischen Stadt Alexandria anlegte, ließ Ptolemaios I. die Fracht nach Schriftstücken durchsuchen und diese konfiszieren. Damit nicht genug: das geklaute Gut verblieb in der legendären Bibliothek, denn die Angestellten des Königs schrieben die Dokumente ab und brachten nur die Kopien zurück auf die Schiffe. Die Geschichte zeigt: die Ägypter waren sich der Bedeutung der materiellen Seite der Papyri wohl bewußt, denn diese bürgte für die Echtheit der Dokumente. Innerhalb der Kulturgeschichte des Buchs spielt seine Materialität immer eine wichtige Rolle.

Albert Coers arbeitet mit den materiellen Aspekten des Buchs. Seine Installationen ziehen Verbindungen zur Geschichte vom flächendeckenden Bücherklau unter Ptolemaios I., aber auch zu den immateriellen Wissensspeichern des 21. Jahrhunderts. Heute besteht die Bibliothek von Alexandria auch aus einem riesigen Online-Archiv, man „blättert“ in den digitalisierten Büchern und Manuskripten durch Berühren des Touchscreens. „Umblättern“ – ein Begriff aus einer analogen Welt. Albert Coers´ sorgsam aufgeschichtete Bücherstapel, seine verbauten Fenster und Durchgänge entstehen vor dieser kulturgeschichtlichen Entwicklung des Buchs und evozieren jenes haptische Ereignis, das angesichts der Digitalisierung seltener wird – eine vielleicht bald anachronistische Erfahrung. Je nach Bauweise der Installation sind verschiedene Aspekte des Buchs freigelegt: der Schnitt, der Buchrücken und das Cover, mit dem jeder Leser oft eine ganz persönliche Erinnerung an ein Buch verbindet. Inhalte sind an Bilder und Optik der Umschläge und damit auch an die Zeittypik gekoppelt, seien es die gelben, mit Kuli bekrakelten Reclam-Hefte aus der Schulzeit, Buchreihen mit Portraits von Autoren, oder jene schwarzen Softcover, die der Suhrkampverlag in den 80er Jahren für die Reihe „Romane des Jahrhunderts“ erfand – metallisch schimmernde Prägelettern, wie man sie bis dahin nur von Science-fiction-Bestsellern und Südstaatensagas kannte.

Sinnliche Aspekte und Erinnerungsassoziationen spielen eine wesentliche Rolle in Coers´ zweiteiliger Installation Unschuld des Werdens (2010). Beide Teile bestehen aus Kinderbüchern der 50er bis 70er Jahre, der eine erscheint als eine Art Höhle oder Iglu. Die verblichenen Buchrücken und die Titelzeilen – häufig in Schreibschrift – geben einen Hinweis auf die Zeit, aus der die Bücher stammen. Sie evozieren frühe Leseerlebnisse: Figuren auf dem Cover wurden zu Komplizen, stundenlang konnte man in einer anderen Welt versinken – wie etwa Bastian, Hauptfigur von Die Unendliche Geschichte, der auf einem Dachboden ein Buch findet, dessen Protagonist er selbst wird. Albert Coers spielt mit seiner Installation auf ein Leseereignis an, das von der Unschuld der Entdeckung motiviert ist — ein nicht nach Anwendungskriterien ausgerichteter Leseakt. Ein Leser, der erleben will, nicht Wissen sammeln.

Doch Unschuld des Werdens bekommt vor dem Hintergrund der Entstehungsgeschichte und des Ausstellungsorts einen ambivalenten Charakter: Albert Coers verwendete einerseits seine eigenen Kinderbücher, andererseits Bände der „Internationalen Jugendbibliothek“ in München. Die Installation wurde im Haus der Kunst, bekanntermaßen ein Bau mit NS-Vergangenheit, gezeigt. Am selben Ort beschäftigte sich 1948 die erste Nachkriegsausstellung mit Kinder- und Jugendbüchern, die heute zum Gründungsbestand der Internationalen Jugendbibliothek gehören. Die Ausstellung hatte damals zum Ziel, den extrem vorbelasteten Ort neu zu besetzen und eine historische Markierung zu hinterlassen. Die von Albert Coers verwendeten Bücher erscheinen daher als Zeitzeugen für die Geschichte des Ausstellungshauses und für jene Umbruchsära in der Nachkriegszeit.

Der andere Teil der Installation warf einen Schattenriß an eine Wand im Eingangsbereich des Hauses der Kunst: eine Schreibtischlampe aus der Nachkriegszeit war so positioniert, daß sie eine Buchreihe beleuchtete und deren Schatten gleichzeitig ins Monumentale verzerrte. In der dunklen Silhouette zeichnete sich das von Paul Troost nach den ästhetischen Prinzipien der Naziarchitektur gestaltete Haus der Kunst mit seiner monumentalen Säulengalerie ab. Unschuld des Werdens als Titeladaption von Nietzsches gleichnamigem Nachlaß liefert ein vielschichtiges Anspielungsgeflecht, in dem kindliche Neugierde ebenso eine Rolle spielt wie ideologischer Machtmißbrauch. Der Titel assoziiert die Kultur- und Erziehungspolitik während, bzw. nach der NS-Diktatur ebenso wie die philosophisch legitimierte Ideologie vom Übermenschen, und schließlich erinnert die Form der Bücherhöhle auch an Scheiterhaufen und brennende Bücherberge.

Mit Bibliotheken zu tun haben sowohl Unschuld des Werdens als auch das Projekt ENCYCLOPEDIALEXANDRINA (2008/ 2009) – das auf eine besondere Recherche zurückgeht: im Titel steckt ein Name, den mehrere Städte tragen. Albert Coers bereiste drei davon: das bekannte ägyptische Alexandria, die amerikanische Stadt im Bundesstaat Virginia und das italienische Alessandria im Piemont. In den Bibliotheken dieser Städte recherchierte er zum Thema „Alexandria“ und kopierte entsprechendes Material. Eine besondere Pointe: in der Quellenbeschaffung durch Kopien steckt eine Analogie zu jenen Abschriften, die Ptolemaios I. von den geraubten Büchern anfertigen ließ.

ENCYCLOPEDIALEXANDRINA – der Titel des Projekts suggeriert Vollständigkeit. Allerdings war dieser Selbstversuch, ein eigenes, komplettes Archiv über den bekannten Städtenamen herzustellen, natürlich aufgrund der Informationsfülle von Beginn an zum Scheitern verurteilt. Er liefert vielmehr ein Modell für die subjektive – nur zum Teil systematisch entstandene – Erinnerungsenzyklopädie, über die jeder verfügt: das Gedächtnis. Dieses ganz und gar persönliche Archiv wird nach den Gesetzmäßigkeiten des Erinnerns und Vergessens beständig erweitert und demontiert: meist unsystematisch, nicht objektiv, nämlich vor allem auch entsprechend der emotionalen Gewichtung, nicht nach weltgeschichtlicher Bedeutung. Ein Archiv, in dem das Primat der eigenen Biographie gilt.

Astrid Mayerle, Studium Kunstgeschichte und Neuere Deutsche Literaturwissenschaft. Kulturjournalistin, Featureautorin und Hörfunkregisseurin für verschiedene Kunstmagazine und Radiosender wie Deutschlandradio Kultur, ARD, BR. Sie ist Mitherausgeberin der Publikation Ehemaliges KGB-Gefängnis, Leistikowstraße 1, Potsdam.

Astrid Mayerle: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Memory

It was a pretty ruthless enterprise: as soon as a foreign ship laid anchors in Alexandria of Egypt, King Ptolemy I had the freight searched for documents and confiscated them. But this was not enough: the pinched goods stayed in the legendary library where the king’s employees replicated them, bringing only copies back to the ships. This story shows the Egyptians awareness of the material aspect of the papyri as a guarantee of the document’s authenticity. Materiality consistently played an important role within the cultural history of the book.

Albert Coers draws on this aspect as well. His installations connect to the narrative of extensive book theft under Ptolemy, but also to the immaterial archives of knowledge of the 21st century.

Today, the library of Alexandria also exists as a huge online-archive; one “leafs” through the digitalised books and manuscripts by touch-screens; “to turn over” – a concept of the analogue world.

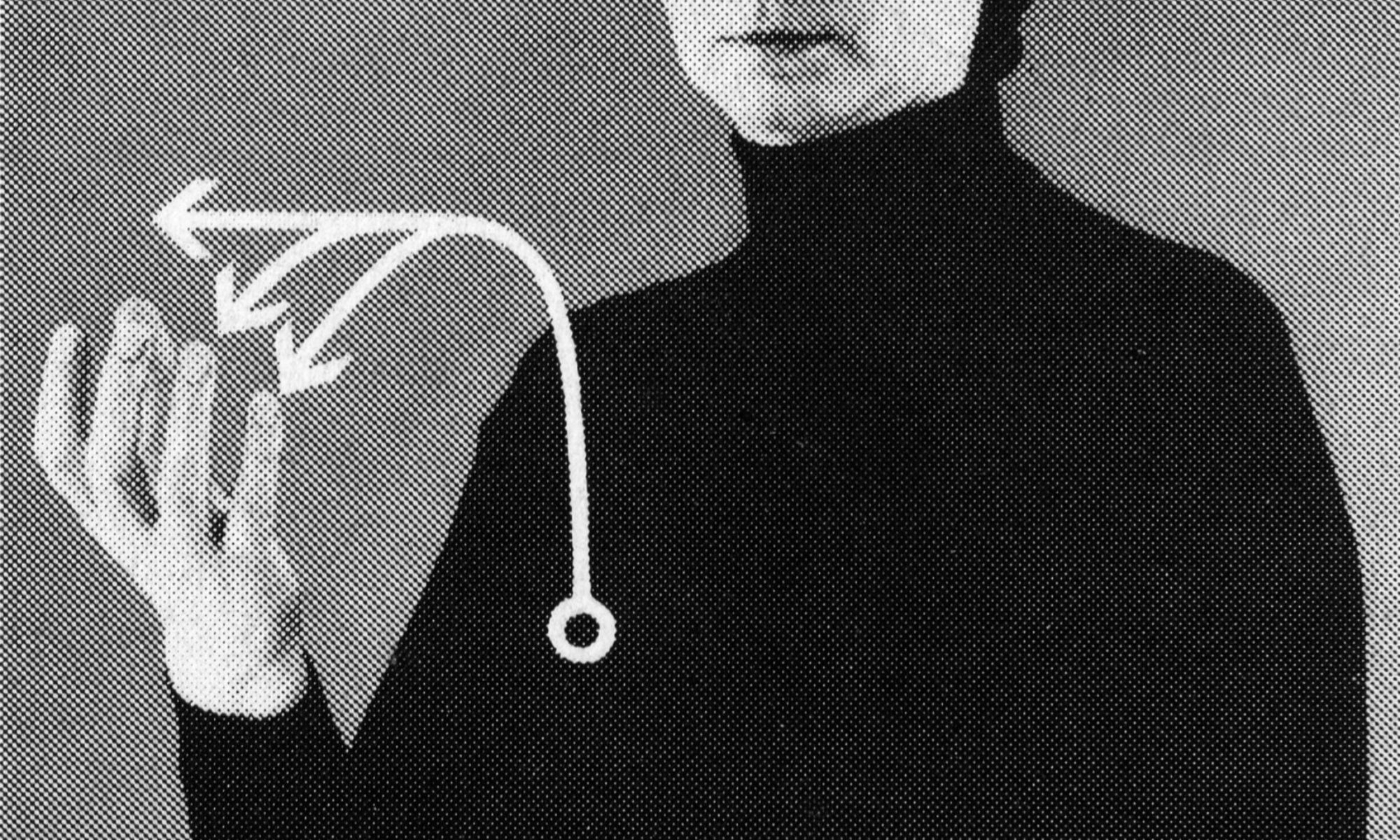

The carefully built piles of books, the obstructed windows and passages of Albert Coers rise in front of this development in cultural history and evoke this increasingly rare haptic moment– which may be soon an anachronistic experience.

According to the construction of the installation, different aspects of the book are exposed: the cut, the spine, and the cover, which connect to the personal memories of the reader. Content is connected to pictures and the look of the covers and therefore to the style of a certain époque; be they the yellow booklets of Reclam editions from schooldays covered with scribbling, book series with portraits of the author, or those soft black covers which Suhrkamp publishers invented in the 80’s for the series “Novels of the Century.” Their metallically gleaming embossed letters previously only seen on Science-Fiction bestsellers and Southern-States sagas.

Sensual aspects and associations of memory play a crucial role in Coers two-part installation Innocence of Becoming (2010). Both parts consist of children’s books from the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s with one part appearing in the shape of a grotto or igloo. The faded spines and their titles – often in cursive script – give a hint to the era the books come from. They evoke early experiences of reading: characters from the cover became accomplices, in a world one could become immersed in for hours– like Bastian, the main character of The Neverending Story, who finds a book in the attic, of which he becomes the protagonist. Albert Coers alludes to a moment of reading motivated by the innocence of discovery – an act of reading not determined by criteria of use, a reader who wants to experience and not to collect knowledge.

However, against the background of its development and the location of the exhibition, Innocence of Becoming assumes an ambivalent character: Albert Coers appropriates from his own childhood, as well as volumes from the International Youth Library in Munich. The installation was shown in the Haus der Kunst, a building with a notorious NS past. It was here that in 1948 the first exhibition after WWII showed the children and youth books that are now a part of the founding collection of the International Youth Library. The exhibition aimed at readdressing the extremely tainted place while simultaneously leaving a historical mark. The books used by Albert Coers appear both as witnesses for the history of the exhibition building and of the era of change in post-war Germany.

The other part of the installation threw a shadow on the wall near the entrance of the Haus der Kunst: a desk lamp in post-war style was placed illuminating a row of books and at the same time distorting their shadows into the monumental. In the dark silhouette the towering colonnade of the Haus der Kunst emerged, designed by Paul Troost according to the esthetical principles of NS-architecture.

Innocence of Becoming as an adaptation of the title of the collected unpublished works of Nietzsche produces a multilayered complex of allusions in which childlike curiosity plays a similar role as it does in ideological abuses of power. The title is associated with the policy of culture and education during and after the NS-dictatorship, likewise with the philosophically legitimated ideology of the Übermensch. Finally, the form of the cave reminds one of the pyres and burning mounds of books.

Innocence of Becoming as well as the project Encyclopedialexandrina deals with libraries, the latter returns to specific research: the title contains a name shared by a number of cities. Albert Coers has travelled to three of them: the well-known Egyptian Alexandria, the American city in Virginia and the Italian Alessandria in Piedmont. In the libraries of these cities he researched the topic “Alexandria” and photocopied corresponding material. It is worth noting the analogy between the method of obtaining source material by photocopying and the copies of the stolen books made by Ptolemy I.

The title of the project suggests completeness. Nevertheless, this experiment to create an individual, fully comprehensive archive of the well-known name was — naturally — doomed to failure due to the abundance of information. But what is more, Albert Coers’ ENCYCLOPEDIALEXANDRINA forms a model for the subjective, only partially systematically grown encyclopaedia of recollection: the memory. This totally personal archive is continuously enlarged and dismantled according to the principles of recollection and oblivion: mostly unsystematic, non-objective, and above all corresponding to emotional weight, not to historical significance. An archive in which the primacy of the individual biography prevails.

Astrid Mayerle studied art history and modern German literature. She is culture journalist, feature author and radio director for various art magazines and radio stations such as Deutschlandradio Kultur, ARD, BR. She is co-editor of the publication Former KGB Prison, Leistikowstraße 1, Potsdam.