Albert Coers’ Installation Nell’ ombra del monte/Im Berg(Schatten) ist sein Beitrag für die Ausstellung Tanz auf dem Vulkan, zu der er 2010 in die Kunstarkaden (München) eingeladen wird. Ein etwas schwieriger Titel für eine Gruppenausstellung, scheint es mir. Wie nimmt man darauf Bezug ohne illustrativ zu argumentieren und bleibt seiner Arbeit zugleich treu? Coers löst den Bezug zum Ausstellungstitel elegant, exzerpiert für sich daraus den Begriff der Gefahr und das Motiv des Berges, und macht sich dann mit seiner Idee unabhängig an die Installation.

Nell’ ombra del monte ist eine ebenso schlicht gebaute wie wirkungsvolle Konstruktion. Die offene Inszenierung der Mittel wird mit der Mystik des aus ihr entstehenden Bildes in eins gesetzt: Als Material dienen Coers ein Tapeziertisch, Bücher, die er auf diesem Tapeziertisch stapelt, und eine Schreibtischlampe, die er davor montiert. Das ist alles, was nötig ist, um das dunkle Schattenbild eines Bergmassivs an die Galeriewand zu zeichnen, dieses zugleich durch die Auswahl der einzelnen Bücher mit Zeit- und Bergsteigergeschichte aufzuladen und zudem auch einen ganz persönlichen Bezug zur eigenen Künstlergeschichte zu setzen.

Nell’ ombra del monte hat eine Vorgeschichte: 2009 ist Albert Coers zu einer Einzelausstellung ins Künstlerhaus München eingeladen. Es steht ihm frei, ein beliebiges Projekt zu entwerfen, einzige Vorgabe ist, daß er sich dabei auf den Ort selbst bezieht und eine spezifische Arbeit entwickelt. Coers, der seit vielen Jahren mit Büchern als Material für seine Installationen arbeitet, bittet die Organisatoren des Künstlerhauses um einen Hinweis, ob es eine Bibliothek gibt bzw. ob man ihm Bücher überlassen könnte, die mit dem Haus in Beziehung stehen. So kommt es zur Empfehlung der privaten Bibliothek des verstorbenen Architekten Karlheinz Lieb, der nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg beim Wiederaufbau des Künstlerhauses mitgewirkt hatte. Sie existiert noch in der ehemaligen Wohnung des Architekten und wird von den Kuratoren betreut.

Auffallend an der Büchersammlung von Lieb sind die zahlreichen Bergbücher, unter anderem Literatur zu den großen Pamir-Expeditionen, die der Deutsche und Österreichische Alpenverein seit 1913 unternommen hatte. Der Pamir ist ein Hochgebirge in Zentralasien, das Kirgistan, China, Afghanistan und Tadschikistan verbindet. Abbildungen dieses Bergmassivs waren für Coers der Anstoß, aus der vorgefundenen Literatur in den Fensternischen der Werkstatt für Lithographie ein Bücherbergmassiv zu bauen, das eine Fortsetzung der aufgeschichteten Drucksteine inszeniert. Während Coers an seinem Eingriff zunächst vor allem das Motiv der Schichtung interessierte, war ein überraschender Nebeneffekt, daß die Installation ein Schattenbild produzierte, das dem Künstler ein weit „bergigeres“ Bild eines Höhenzuges auf den Boden zu zeichnen schien, als es die Installation selbst vermitteln konnte.

Es war also eine zufällige Entdeckung, die das Thema des Schattenbildes ab nun bewußt bei den Buchinstallationen präsent werden ließ. Bei der folgenden Ausstellung in den Kunstarkaden sollte die Installation nicht mehr primär im Vordergrund stehen, sondern selbst zum Medium der Bilderzeugung werden. Das Wechselspiel zwischen Konstruktion, Illusion und Desillusionierung stellt Coers dort erstmals in einer ebenso poveren wie pointierten Weise vor.

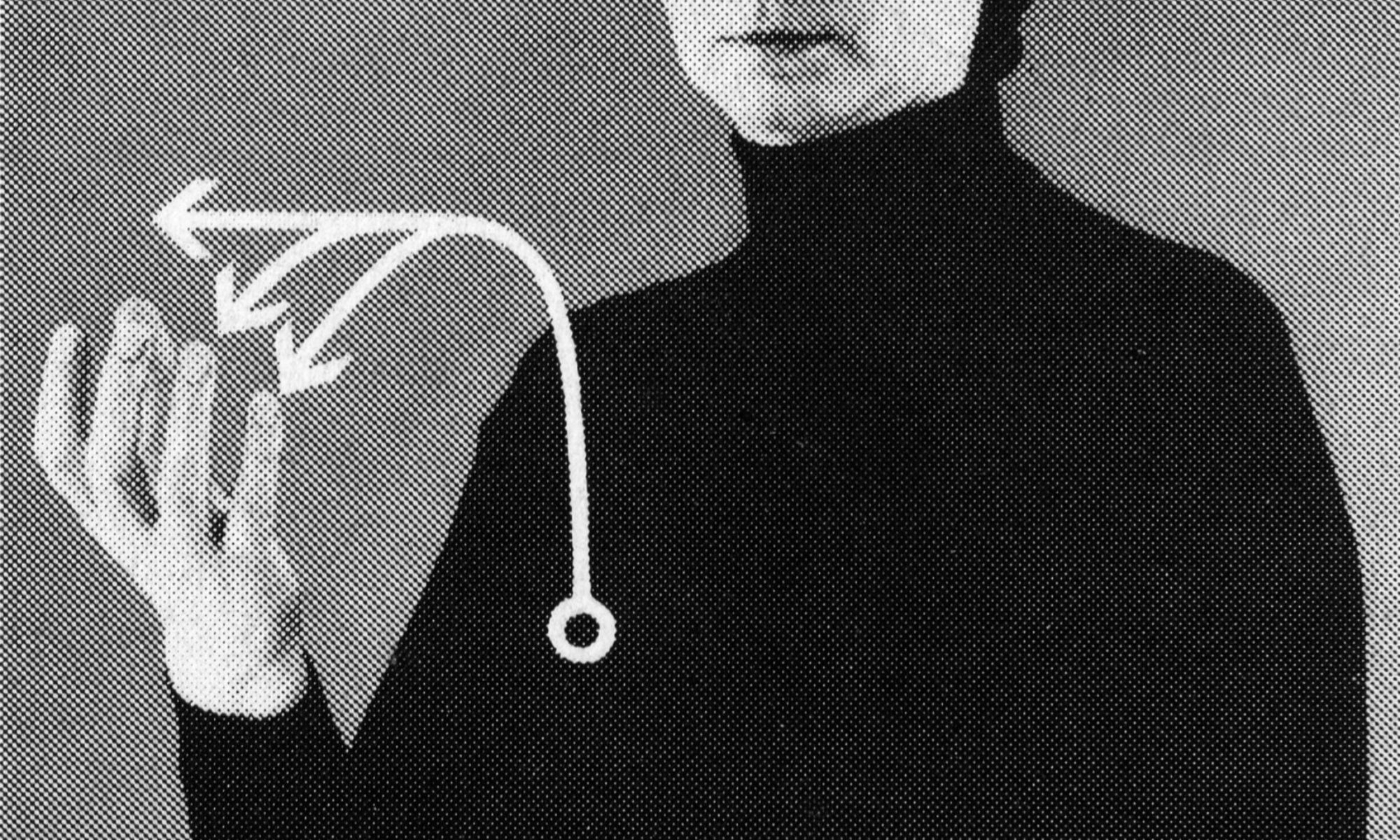

Jeder kennt das Kinderspiel, bei dem man durch eine bestimmte Haltung der Hand oder beider Hände Schattenbilder erzeugen kann, die einen Hasen, einen fliegenden Adler, einen Hundekopf, Hirsch oder Schwan an die Wand werfen. Faszinierend daran ist eben dieses Spiel des nicht identischen Bildes, denn während man beim Maître des Illusions nichts als seine Hände sieht, läßt deren Schatten eine ganze Batterie von wilden Kreaturen entstehen. Die absurde Situation, daß etwas sichtbar ist und doch nicht existent ist, ist ein unumgänglicher Reiz. Anders herum bleibt die Illusion immer zugleich transparent.

Und so beläßt auch Coers in der Ausstellung alles so wie es eben ist: der schmale Tapeziertisch biegt sich unter dem Gewicht der Bücher und die Schreibtischlampe lagert unprätentiös vor den aneinandergelehnten Publikationen, die von dem gleißenden Licht der Glühbirne getroffen werden. Hinter dieser Szenerie aber thront ein dunkles Gebirge, das das ganze Pathos seiner Symbolik, die Tragödien und die Heldenerzählungen seiner Bezwingung in sich schwingen läßt. Ein wunderbar surreales Kunst-Stück.

Neben Nell’ ombra del monte inszeniert ein weiteres Werk, das Coers ausstellt, die Anwesenheit des Abwesenden. Auch in der Serie I TITOLI SOLI sind die Bilder – oder besser die Graphiken – nicht primär identisches Abbild, sondern verweisen kunstvoll auf etwas, auf das Coers Bezug nimmt, das er in der Hand hatte, mit dem er gearbeitet hat und das zurückgekehrt ist in den Kontext, aus dem er es für seine künstlerische Arbeit entliehen hatte.

In I TITOLI SOLI fixiert Coers mit einer traditionell wissenschaftlichen Methode der Dokumentation den Verlust. Wie in der archäologischen Frottagetechnik vorexerziert, reibt Coers geprägte Titel und Bilder von Buchdeckeln und Buchrücken durch aufgelegtes Papier ab, und kombiniert diese Abriebe bei der Hängung so, daß sich aus ihren Beziehungen eine neue Erzählung entwickelt. Auf jede Vorlage wird mit der passenden Schraffurtechnik reagiert, und auch die Wahl der Bücher ist kein Zufall. Mit den Prägedrucken läßt sich ein spezifisches Zeitgefühl vermitteln, denn sie sind eine gestalterische Erscheinung, die ihre Hochzeit vor allem zwischen den 1920er und 1950er Jahren hatte. Auch in I TITOLI SOLI spielt das Pathos der Titel und ihrer Bildmotive auf Existentielles an und nicht zuletzt auf eine Geschichte, die das Pathos bis hin zu extremsten Verfallserscheinungen getrieben hat.

Nur so viel noch: Albert Coers war und ist selbst ein begeisterter Bergsteiger, und eben dieses Spiel zwischen Herausforderung und Gefahr, zwischen Bezwingung und Absturz, übt auch auf ihn einen magischen Reiz aus. In der Arbeit ist dies übersetzt in eine valentineske, aber ebenso surreale wie kritische Einladung zu einer Wanderung durch künstliches Gebirge und dessen Steilwände, Abgründe und Ausprägungen.

in: Albert Coers: I SOLITI TITOLI, Bielefeld 2011, S. 38 ff.

Diana Ebster, *1966. Studium der Kunstgeschichte, Geschichte und Archäologie in Eichstätt und Bochum. Freie Mitarbeit u.a. bei hArtware projekte Dortmund. Nach einem Volontariat an der Staatlichen Kunsthalle Baden-Baden freie Kuratorin u.a. des lothringer13_laden, der Osram Gallery und des ZKMax/Maximiliansforums in München, seit 2007 Mitarbeiterin des Kulturreferats der Landeshauptstadt München im Team Bildende Kunst.

Diana Ebster: The Call of the Mountain

The installation “Nell’ ombra del monte/In the Mountain(Shadow)” by Albert Coers is his contribution to the exhibition “Dancing on the Volcano” for which he was invited 2010 in the Kunstarkaden, Munich. A somehow difficult title for a group show as it seems to me: how one can possibly relate to without being illustrative and be faithful to his work at the same time? Coers resolves the relation to the title of the exhibition elegantly, excerpts for himself the concept of danger and the motive of the mountain, and then autonomously sets out with his idea for the installation.

“Nell’ ombra del monte” is an installation, as simply constructed, as it is effective. The open staging of its means is put in one with the magic of the emerging image: as material Coers uses a pasting table, book which he staples on this table, and a desk lamp, which he sets up in front. That is all what is necessary to draw on wall of the gallery the dark shadow of a mountain range, to charge it by the selection of the single books with recent history and the history of alpinism. Moreover, it connects it in a very personal way to the individual history of an artist.

Nell’ ombra del monte has a background: In 2009 Albert Coers is invited for a single show in the Künstlerhaus Munich. It is left to him to do a project whatsoever, only demand is to refer to the place itself and to develop a specific work. Coers, who since many years works with books as material for installations, asks the curators for information about a library respectively any books connected to the house that could be handed over to him. They suggest the private library of Karlheinz Lieb, an architect who had worked on the reconstruction of the Künstlerhaus after the Second World war. It still exists in the former apartment of the recently deceased architect and is looked after by the curators.

What attracts the attention in Lieb’s collection of books are the numerous books on mountains, among other literature on the big expeditions to the Pamir undertaken by the German and Austrian Alpine Association since 1913. The Pamir is a mountain range in Central Asia, connecting Kyrgyzstan, China, Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Images of this massif were a motive for Coers to build a massif of books from the found literature located in the window recess of the lithographic printing office, staging as a continuation of the stacked printing stones. While Coers in his intervention first was interested in the visual theme of stratification, an surprising side-effect came up when the installation produced a silhouette which appeared to the artist to draw a far more “mountainous” image of a mountain range on the floor than the installation itself could convey/portray.

Thus, it was a casual discovery that let become the theme of the shadow image prevalent, from now on consciously. In the following exhibition in the Kunstarkaden, the installation should not be primarily prominent/in the spotlight, but serve itself as a medium for creating images. The interplay between construction, illusion and disillusion Coers presents there the first time, as simply/minimalist as to the point/precisely.

Everybody knows the child play, where one can create silhouettes by a certain position of one or both hands projecting at the wall a hare, a flying eagle, a dog’s head, a deer or a swan. What is fascinating about that is the play of the non-identical image, as while one sees nothing but the hands of the Maître des Illusions, their shadow brings a whole bunch/army of wild creatures to live.

The absurd situation something being visible and non-existent is an inevitable appeal/attraction. The other way round the illusion remains always transparent at the same time. Therefore, Coers leaves everything in the exhibition as it just might be: the slender pasting table bows under the burden of the books and the desk lamp lays without pretension in front of the publications leaning one against the other which are struck by the glistening light of the bulb. Nevertheless, behind this scenery thrones a dark range of mountains that implicates the entire pathos of its symbolism, the tragedies and epopees of its conquest. A marvellously surreal piece of art.

Besides „Nell’ ombra del monte“an other exhibited work displays the presence of the absent. In the series „I titoli soli“ the pictures –or better drawings- are not primarily an identical image but point artfully to something Coers is referring to, which he had in hand, he had worked with and which has returned in the context from which he had loaned it for his artistic work. In „I titoli soli“ Coers retains the loss applying a traditional scientific method of documentation. As demonstrated by the archaeological technique of frottage, Coers rubs embossed titles and images of covers and spines through paper he has applied, and combines these rubbings on the presentation/hanging in order to develop by their relations a new narrative. To every model, he responds with an adequate technique of hatching, and the selection of books is not arbitrary, either. The embossed printings allow imparting a specific spirit of time for they appear as a matter of design that had its heyday mainly between the 1920’s and the 1950’s. In „I titoli soli“ the pathos of the titles and their motifs alludes to something existential and not least to a history that carried/took pathos to heaviest symptoms of decline.

Only one more point: Albert Coers has been and still is a passionate mountain climber and it is exactly this play between challenge and danger, conquest and fall that holds for him a magic attraction. In the piece, it is translated in a valentineske, but in the same way both surreal and critic invitation to a hike through artificial mountains and their steep faces, abysses and peculiarities/shapes.

in: Albert Coers: I SOLITI TITOLI, Bielefeld 2011, S. 38 ff.

Diana Ebster, *1966. Studied History of Art, History and Archaeology in Eichstätt and Bochum. Freelance a.o. with hArtware projects Dortmund. After a traineeship at Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden freelance curator a.o. of lothringer 13_laden, Osram Gallery and ZKMax Munich, since 2007 at the Department of Arts and Culture ot the City of Munich.