(for English version: please scroll down)

Wer als Autor Ausstellungen mit zeitgenössischer Kunst besucht, darf heutzutage damit rechnen, eigene Bücher als Teil eines Kunstwerks wiederzufinden. Viele Künstler, von Thomas Hirschhorn über Pipilotti Rist bis zu Georges Adéagbo, verwenden Bücher nämlich als Bestandteile meist groß angelegter Installationen. Ähnlich wie in Buchhandlungen oder Museumsshops sucht der Autor also – unverhohlen eitel – danach, ob auch einer seiner Titel ausgelegt, aufgestellt oder gestapelt wurde. Und er freut sich zuerst, wenn er sein Werk entdeckt.

Dann jedoch beginnt er sich zu fragen, was den Künstler dazu bewogen haben könnte, neben – meist vielen – anderen Büchern auch sein eigenes auszuwählen. Um eine Antwort auf diese Frage zu bekommen, schaut er, welche Titel sonst noch in das jeweilige Kunstwerk aufgenommen wurden. Waren es formale Kriterien wie Coverfarbe oder Größe, die die Entscheidung beeinflußten, ging es um den Titel oder gar wirklich um das Thema oder eine These? Meist jedoch gelangt der Autor bei solchen Betrachtungen zu keinem befriedigenden Ergebnis, sondern eher zu der Befürchtung, es sei bei der Zusammenstellung recht wahllos und zufällig zugegangen. Und nicht bloß ein Autor, sondern jeder Rezipient, der sich nur ein wenig mit Büchern auskennt, wird von ähnlichem Unbehagen befallen. Er spürt, daß da kein Kenner am Werk war, sondern entweder jemand, der Bücher als beliebigen Werkstoff, ähnlich wie Ziegelsteine oder Dachlatten, verwendet hat, oder aber, noch schlimmer, jemand, der sich, meist im doppelten Sinn des Wortes, als Hochstapler betätigt – der nämlich Bücher aufeinandertürmt, die er nicht gelesen hat, von denen er jedoch glaubt, sie würden Eindruck machen oder ein Thema kritisch, ironisch, bedeutsam in Szene setzen. Autorennamen und Buchtitel werden dann zu Ersatzmitteln einer ernsthaften, auch formal stimmigen Auseinandersetzung mit einem Sujet. Und sie werden zu Statussymbolen, wobei der Künstler kein besseres Bild abgibt als der vielzitierte Spießer-Zahnarzt, der seine Klassiker in Leder gebunden über dem Kamin stehen hat. Mit anderen Worten: Wer nur ein bißchen bibliophil ist, wird an den meisten Arbeiten zeitgenössischer Künstler, in denen Bücher eine Rolle spielen, nur wenig Vergnügen finden.

Die Arbeiten von Albert Coers gehören zu den wenigen Ausnahmen. Und der Grund dafür ist einfach zu benennen: Coers ist selbst ein großer Bücherfreund und Literaturkenner. Er baut seine Installationen mit Büchern, weil ihm wohl kein anderes ‘Material’ ähnlich vertraut ist. Wo andere mit Bücherstapeln dilettieren, halten sie bei ihm einer genaueren Prüfung stand. Man erkennt schnell, daß die gewählten Bücher gut zusammenpassen. Selbst wenn sie aus verschiedenen Bereichen stammen, unterschiedlich alt und nicht gleichermaßen gut erhalten sind, entsteht ein plausibler Gesamteindruck. Statt annehmen zu müssen, der Künstler habe einfach ein paar Ausschußkisten von einem Antiquariat aufgekauft oder auf Flohmärkten schnell eine bunte, exquisit anmutende Auswahl zusammengesammelt, hat man das Gefühl, eine gut sortierte, langsam gewachsene Bibliothek vor sich zu haben.

Das ist alles andere als nebensächlich. Erst so nämlich beginnen die Installationen etwas zu erzählen – und mehr zu sein als bloße Anhäufungen. Wie es immer noch der sicherste Weg ist, in einer fremden Wohnung das Bücheregal zu inspizieren, um möglichst viel über die dort lebende Person zu erfahren, geben auch die bizarr, riskant oder einfach nur lustig angeordneten Bücher der Installationen von Albert Coers zahlreiche Anhaltspunkte, um sich ein Bild von ihrem mutmaßlichen Besitzer zu machen. Dabei tragen die Formen, zu denen die Bücher arrangiert sind, natürlich ebenfalls zu den Vorstellungsbildern bei. So vermittelt sich bei den beiden im Jahr 2004 aus der Privatbibliothek des Künstlers entstandenen Arbeiten trullo I und trullo II der Eindruck, hier habe ein introvertierter, an vielen Formen von Hochkultur interessierter Mensch ein zeltartiges Gebäude aus seinen Büchern errichtet, um sich von der für ihn oft zu ruppig-kulturlosen Außenwelt abschirmen zu können. Die Fluchten aus dem eigenen lauten Alltag, die das Lesen oft bietet, haben sich nun also in einer nomadischen Behausungsform materialisiert, die freilich nicht ohne Tragik ist: Wer sich in das Bücherzelt begibt, liegt nicht nur in leseuntauglichem Dunkel, sondern kann auch keines der ihn umgebenden Bücher rezipieren. Sobald man nur eines an sich heranzöge, stürzte das gesamte Gebilde zusammen; man wäre unter Hunderten von Büchern begraben.

Auch bei anderen Installationen wendet Coers Eigenschaften, die Büchern gerne zugeschrieben werden, paradox ins Gegenteil. Bei biblioteca privata II, ebenfalls aus dem Jahr 2004, stapelte er Bücher so lange in eine Fensternische, bis so gut wie kein Licht mehr in den Raum kam (es gab dort nur ein Fenster). Wo Bücher sonst den Ausblick in fremde Welten bieten, verstellten sie nun also die Möglichkeit, den eigenen Horizont zu erweitern.

Diese Beispiele zeigen: So bibliophil Albert Coers auch sein mag, er artikuliert zugleich eine Skepsis gegenüber einer buchgläubigen Haltung. Vielmehr empfindet er die Mengen an Büchern, die um sich hat, wer einem bildungsbürgerlichen Ethos anhängt, auch als bedrohlich. Am stärksten wurde dies wohl bei collezione privata (2002) erfahrbar. Bei dieser Installation präsentierte Coers den gesamten Kellerinhalt eines Sammlers von Büchern sowie von anderen, oft mit Bildern bedruckten Papieren. Der Galerieraum war voll von Stapeln, überquellenden Regalen, chaotischen Häufen. Der Besucher spürte mit wachsender Beklemmung, wie die Sehnsucht nach geistiger Freiheit, die die Inhalte all der Druckerzeugnisse eigentlich repräsentieren und auch fördern, in ein Gefühl von Ohnmacht umschlägt, sobald mehr aufgehäuft ist, als noch überblickt und erschlossen werden kann. Coers reflektierte diese Ohnmacht, indem er an einer Wand der Galerie ein weiteres Regal anbrachte, in dessen Fächer er ausgewählte Stücke aus der Text- und Bilderflut legte. So beruhigend dieser Versuch einer Ordnung wirken mochte, so wenig genügte er doch, um die Unruhe zu bannen, die die überbordende Überfülle im restlichen Raum, nun im Rücken des Besuchers, bereitete. Das Bemühen um Systematisierung scheiterte also – und es blieb bewußt, wie leicht die Verheißungen eines Mediums – hier: des Buchs – von diesem selbst zunichte gemacht werden können.

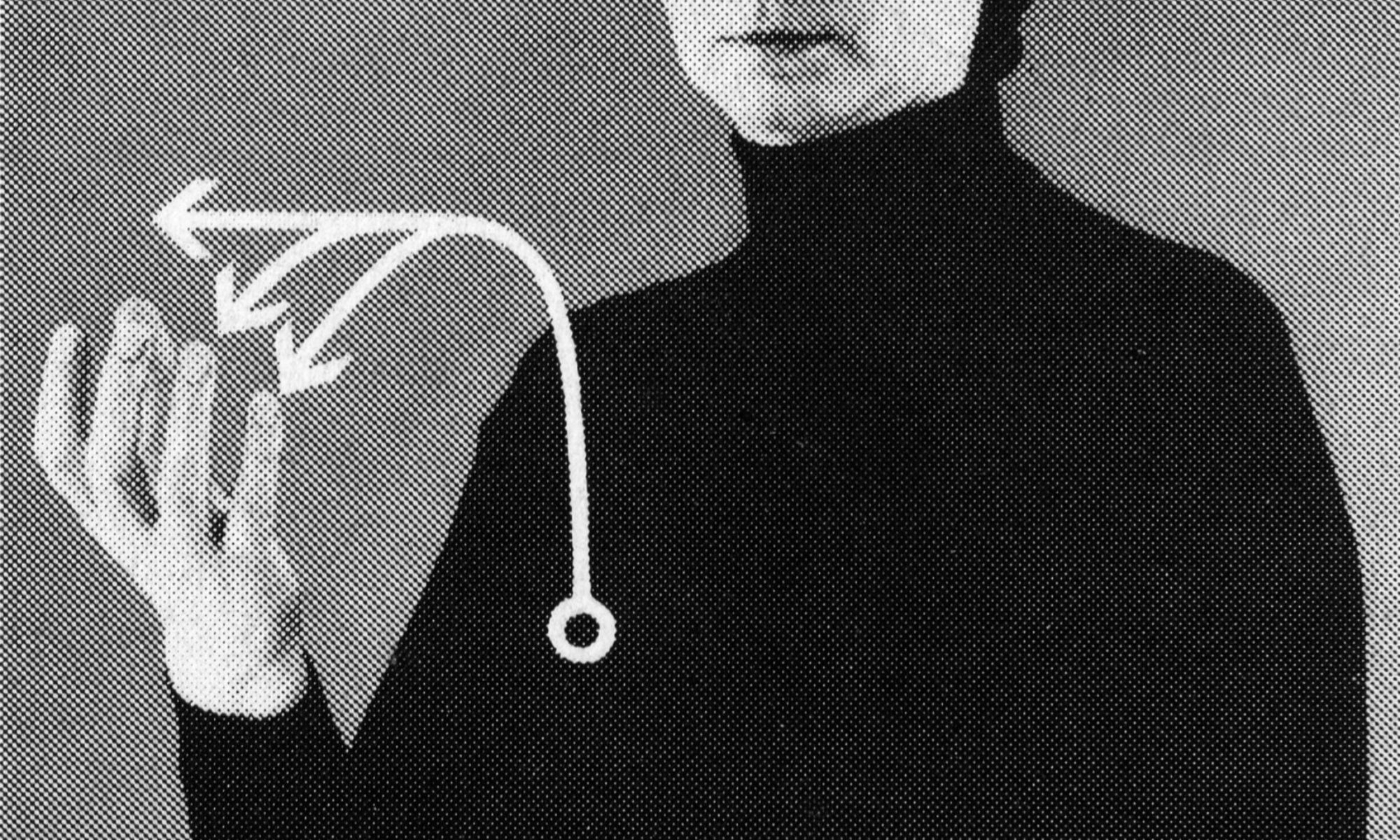

In viel kleinerer Dimension, aber dafür bildhaft klar brachte Albert Coers seine ambivalente Haltung gegenüber der Buchkultur bei Arbeiten wie pila (2004) oder colonna portante (2004) zum Ausdruck. Hier legte er jeweils Bücher so übereinander, daß sich ein höchst labiler Stapel ergab. Auf einen Blick wurde klar: Nur eine leichte Berührung, ein Windstoß, die geringste Erderschütterung brächte den Stapel zum Einsturz. Aus einem Ort immaterieller Schätze würden die Bücher dann schlagartig zu einer Masse lästigen Gewichts.

Wolfgang Ullrich, geb. 1967. Studium der Philosophie, Kunstgeschichte, Wissenschaftstheorie und Germanistik. Freiberuflich tätig als Autor, Dozent, Unternehmensberater. Assistent an der AdbK München. Gastprofessor an der HdbK Hamburg, 2006 bis 2015 Professor für Kunstwissenschaft und Medientheorie an der Staatlichen Hochschule für Gestaltung Karlsruhe. Seither freiberuflich tätig in Leipzig als Autor, Kulturwissenschaftler und Berater. Publikationen zu Geschichte und Kritik des Kunstbegriffs, modernen Bildwelten und bildsoziologischen Fragen sowie zu Wohlstandsphänomenen.

Risky Book Culture

An author attending exhibitions of contemporary art may expect to find his own books as a part of an artwork. Many artists from Thomas Hirschhorn to Pipilotti Rist and to Georges Adéagbo use books as elements of installations of grand dimensions. As in bookshops or shops of museums the author – unveiled vain- searches for whether there are any of his titles laying out or piled up. He is only happy when he glances and discovers one of his works. But then he starts asking, what might have been the artist’s motivation for choosing among the many other books, also his. In order to get an answer for this question, he looks, what other titles have been included in the respective work of art. Was it formal criteria as the colour of the cover, or size, that influenced the decision, was it about the title or really about the theme or a thesis?

In most cases, although, the author doesn’t reach to a satisfying result, but more likely he is afraid, that the composition might have been quite indiscriminate and casual. And not only the author, but every recipient who knows even a little about books, is overcome by similar unease. He feels that there was no connoisseur working, but either somebody who used books as any material, like bricks or pickets, or, worse, somebody who is an Hochstapler, an impostor [German “Hochstapler”-somebody who piles up something in the high] – mostly in the double sense of the word – who piles up books that he hasn’t read, that he thinks they could make impression or put on a show with a critical ironic or meaningful sense. Names of authors and titles become substitutes of a serious and also formal mood dealing with a subject. They also become symbols of status, with the artist playing no better role than the often quoted petty bourgeois dentist, who has his classics coated in leather standing above the fireplace. In other words: those who are only a little bibliophile, are going to find little pleasure in most works of contemporary artists in which books play a part.

The works of Albert Coers are among the rare exceptions. And the reason for that is easy to say: Coers is a great friend of books and a connoisseur of literature. He builds up his installations with books because probably no other material is so familiar to him. Where others dabble with piles of books, his collections sustain a closer examination. One quickly realises that the books chosen fit well together. Even if they’re from different sections, of different ages and not all equally well preserved, a plausible impression of a whole is created. Instead of being compelled to presume, the artist had been simply buying a few boxes of a second-hand-bookstore or collecting at a flea-market hastily a multicoloured, exquisite appealing mixture, one feels as if one is in front of a well-sorted, steadily grown Library.

That is far from being unimportant. Only in this way the installations begin to tell something – and to be more than mere accumulations. Like it is still the most secure way in a foreign apartment to go to check the bookshelf in order to learn as much as possible about the person that lives there, also the bizarre, hazardous or only funny arranged books of the installations of Albert Coers give many clues for putting together an image of his probable owner. Furthermore, the forms, in which the books are arranged, contribute to the imagination. So the works created from the private library of the artist trullo I and trullo II communicate the impression of an introverted, but a person interested in the many forms of culture, having erected an tent-like building with his books in order to protect himself from the for him often to dull and uncultured outside world. The refuge from their own loud daily life, that reading often provides, has materialised in a nomadic housing, which however, is not without tragedy: those who enter the tent of books, not only lies in the darkness that makes reading impossible, but also can’t read any of the books which are surrounding him. As soon they would remove one single book, the whole building would crash burying him under hundreds of books.

Also with other installations Coers turns qualities that often are referred to books paradoxically in the opposite. In biblioteca privata II, dating also from 2004, he piles up books in the frame of a window until the room hardly had any light (there was only one window). Where books provide an outsight to foreign worlds, now they’re blocking the possibility of enlarging one’s horizon.

This examples show, that Albert Coers, as bibliophile he might be, articulates a sceptic point of view to an idolatry of books. What is more, he feels the threat that emanates from the amount of books with which one is surrounded, for those who claim the ethos of middle-class-education. The strongest experience of this kind one has with collezione privata (2002). In this installation Coers presented the whole content of a cellar room of a collector of books and other papers, often printed with images. The space of the gallery was full of piles, of over brimming scaffolds, chaotic heaps. The visitor felt with growing anxiety, how the yearning for intellectual freedom, that the content of all the publications represents and also favours, turns into a feeling of powerlessness, as soon as more is accumulated than can be taken in or absorbed. Coers reflected this helpless feeling by displaying on a wall in the gallery a shelf and putting there pieces selected out of the flood of texts and images. So quieting this attempt of an order might have be, so little did it suffice to ban the restlessness coming from the overflowing abundance in the rest of the room, only behind the visitor. The endeavour to systemise things failed — and it remained conscious, how easy the promises of a medium – here: of the book – can be annihilated by itself.

In much smaller dimension, but metaphorically clear Albert Coers expressed his ambivalent position towards the culture of books with works like pila (2004) or colonna portante (2004). Here he laid books on and over another creating a most unstable pile. At first glance it was clear, that only a soft touch, a gust of wind, the slightest shake of the earth would bring cause the pile to crash down. The books would be transformed abruptly from a place of immaterial treasure into a mass of irritating weight.

Wolfgang Ullrich, born 1967. Studied Philosophy, History of Art, Theory of Science and German Literature. Freelance author, consultant, lecturer. Assistant teacher at the AdbK Munich, visiting professor at the HdbK Hamburg, 2006–2015 professor for Science of Art and Theory of the Media at the HfG Karlsruhe. Publications on history and criticism of the concept of art, and questions regarding the sociology of images, on phenomena of prosperity.