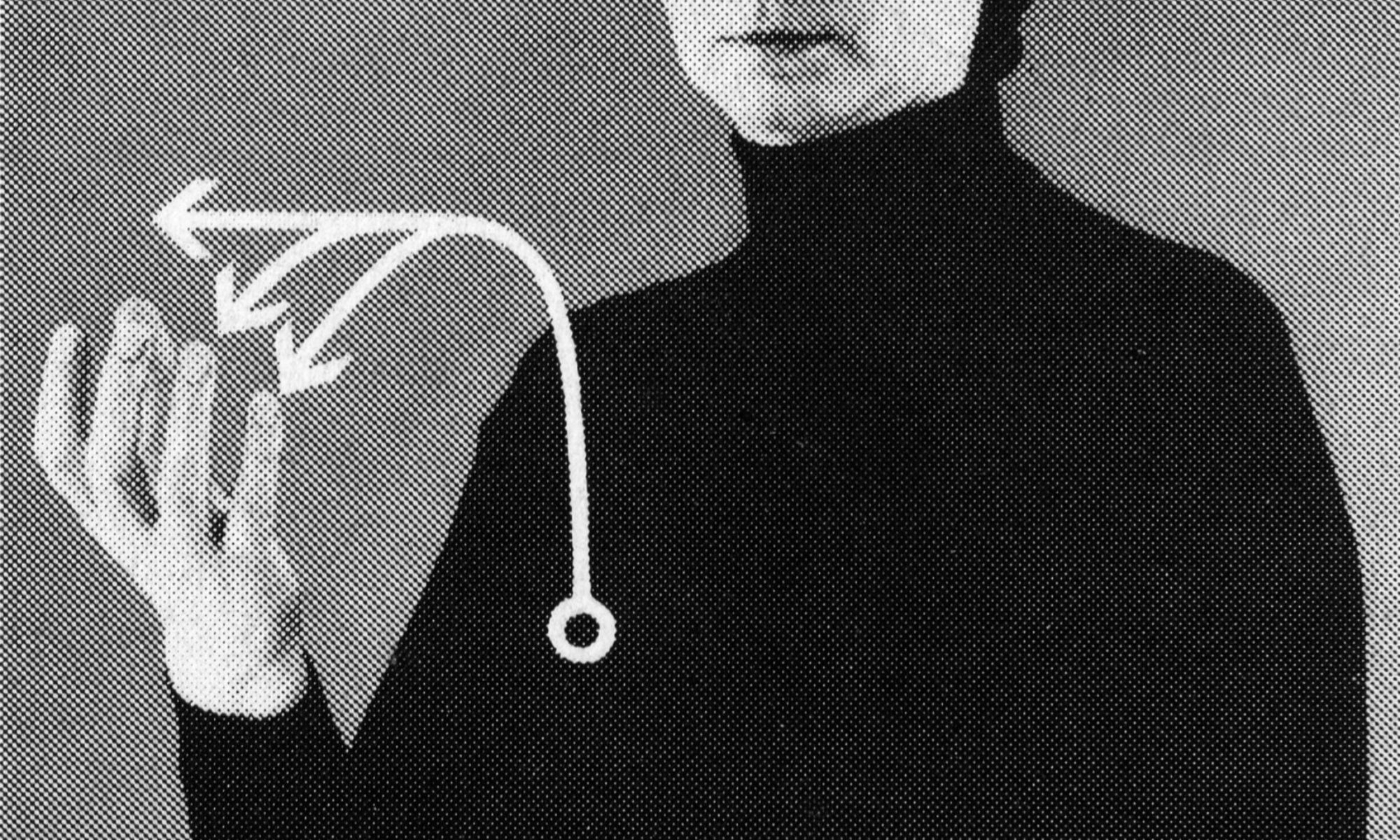

Kleine Bibliotheksgeschichte, 2021, 18 x 15 x 7 cm

Yellow Press, ep.contemporary, Berlin, 2021

books, Galerie Vincenz Sala, Berlin, 2022

Beim Bodenwischen fielen Reclam-Bände aus dem allzu dicht bestückten Regal. Einer davon landete im Wassereimer – der GAU! – die „Kleine Bibliotheksgeschichte“ von Uwe Jochum, die ich 2005 gekauft und kursorisch gelesen hatte. Schnell aus dem Wasser gefischt, war der Band trotzdem feucht, die Seiten klebten zusammen. Was tun? Die Seiten mit Papier abdecken, das die Feuchtigkeit aufsaugt. Ich nahm einen Band mit Schillers Werken und schlug jede Seite des nassen Buches in eine Seite daraus ein, presste beides. Beide Bücher gingen so eine enge Verbindung ein, wurden zu einem Objekt.

Der Schiller-Band erwies sich dabei als passend, auch jenseits der Dramatik der Texte: ein Fundstück, aus einer Corona-Ausmist-Bücherkiste auf der Straße, mit schwarzem Einband, nur eine verblichene Nummer auf dem Rücken. Ein Bibliotheksexemplar. Hinten eingeklebt eine Karte für Eintragungen von Ausleihdaten, zwischen 1926 und 1940. Und, vorne, ein Ex-Libris der Zeppelin-Wohlfahrts-Bücherei in Friedrichshafen, Vorläufer der Stadtbibliothek. Mit diesem konkurrieren private Besitzvermerke. „Stimmt nicht“ steht neben dem Bibliotheksstempel, der überdruckt ist mit einer privaten Adresse. Eine Seite weiter dasselbe, mit dem Zusatz „Dieses Buch habe ich gekauft“ – um dem Eindruck entgegenzutreten, es sei aus der Bibliothek entwendet? Es kommen also öffentliche und private Nutzungen zusammen – die letzte, um ein (gelbes) Bändchen Bibliotheksgeschichte zu pressen – und zu retten.

“Kleine Bibliotheksgeschichte” (A Short History of Libraries), 2021

While mopping the floor, Reclam volumes fell from the overly densely stocked shelf. One of them landed in the water bucket — the MCA! — the “Kleine Bibliotheksgeschichte” (A Short History of Libraries) by Uwe Jochum, which I had bought in 2005 and read cursorily. Quickly fished out of the water, the volume was nevertheless damp, the pages stuck together. What to do? Cover the pages with paper that absorbs the moisture. I took a volume of Schiller’s works and folded each page of the wet book into a page from it, pressing both together. The two books thus entered into a close union, became one object.

The Schiller volume proved to be fitting, even beyond the dramatic nature of the texts: a found object, from a Corona discard book box on the street, with a black cover, only a faded number on the spine. A library copy. At the back, a card for recording lending dates, between 1926 and 1940. And, at the front, an ex-libris of the Zeppelin-Wohlfahrts-Bücherei in Friedrichshafen, forerunner of the city library. Private ownership notes compete with this one. “Not true” is written next to the library stamp, which is overprinted with a private address. One page further on, the same thing, with the addition “I bought this book” – to counter the impression that it was stolen from the library? So public and private uses come together — the last one to press – and save – a (yellow) volume of library history.