Mit der Literatur- und Medienwissenschaftlerin Annette Gilbert habe ich im April 2022 ein Gespräch über das Buch “Books to Do” geführt, wo es auch abgedruckt ist. Der erste Teil des Gesprächs ist hier nachzulesen:

In April 2022, I had an conversation with Annette Gilbert about my book “Books to do”. (English version here)

AG: Zunächst eine Frage zum Titel: „Books to Do“ leuchtet ein, weil es ja ein Buch ist, das du produziert. Gleichzeitig sind etliche der Ideen, die du aufzählst, nicht unbedingt an die Buchform gebunden. Insofern: Warum „Books to Do“ und nicht „Works to Do“?

AC: Mir kommt bei medial diversem Material, bei Bildersammlungen, Fotos, Zeichnungen, Installationen, häufig der Gedanke, daraus ein Buch zu machen. Und oft beziehen sich die Arbeiten ja auf Bücher. Bücher weiterzuspinnen, einen Kommentar zu einem existierenden Buch zu machen: das stammt z.B. bereits von 2014. Dazu kamen zu schreibende Bücher, im Anschluss an meine Dissertation. Es hatten sich immer mehr Buch-Ideen angesammelt. 2019 habe ich angefangen, die zu sammeln und aufzuschreiben, als To-do-Liste. Das hatte auch etwas Befreiendes. Aufschreiben ist ja häufig ein Akt des Externalisierens, des Distanzierens. Gleichzeitig entstand mit der Liste etwas Neues, eine eigenständige Arbeit. Mir gefiel die Selbstreferenz, aus der Liste wieder ein Buch zu machen, in dem die Buchprojekte stehen.

AG: Was an Mallarmés berühmten Ausspruch erinnert: „Alles in Welt ist dazu da, in ein Buch zu münden.“ Das passt zu deinem Oeuvre und ist konsequent. Trotzdem scheint im Titel nicht alles aufzugehen, weil du ja nicht nur Bücher machst, sondern auch Bücher für deine Arbeiten verwendest. Insofern sind einige Werke Works to Do – mit Büchern, sozusagen Wiederverwertung, z.B. Müde Bücher [Nr. 30], die du dann zu Installationen verarbeitet hast. Gleichzeitig eine Selbstreflexion. Insofern ist das ein Kreislauf, wo man vielleicht gar nicht trennen kann zwischen der Entstehung von Büchern und der Verwendung von Büchern.

AC: Man könnte den Titel auch im Sinn einer Aktivierung lesen, „Books to Do“ nicht als zu machende Bücher, sondern „Bücher zum Machen“, Books to Do something with“… Ja, diese Mehrfach-Verwendung oder Verkettung von Büchern, das war eine Idee innerhalb der Books to Do-Reihe.

AG: Du hast deine Dissertation angesprochen, klar, dass das auch dein Denken über dieses Buch oder das Projekt einer Retrospektive mit angeregt hat. Was war die Erkenntnis aus deiner Dissertation zum Katalog als Medium? Was verbindest du mit einer klassischen Monografie, einem Catatalogue raisonneé? Warum hast du diese Form jetzt nicht gewählt? In deiner Liste gibt es bereits Kataloge, eine Monografie von 2002–2008 und 2008-11, dann wäre doch der logische Schritt gewesen: 2011 bis 21! Warum entfernst du dich vom klassischen Modell?

AC: Ich habe gesehen, dass ein Katalog mehr sein kann als nur ein retrospektiv-dokumentarisches Verzeichnis, das Bestehendes möglichst vollständig beschreibt, festhält. Dass man es mit zusätzlichem Text- und Bildmaterial anreichern kann, dass etwas entsteht, was fiktive, prospektive Elemente beinhaltet, was eigenwertiges Künstlerbuch ist. Gleichzeitig bin ich ein Fan des Dokumentarischen und des Katalogs, der Aufzählung, der Liste. Das Buch bietet Nachhaltigkeit, ein Shelf life, von dem man hofft, dass es möglichst lang ist. Ein Lösungsversuch ist, in die Liste der noch zu machenden Bücher einen klassischen Werkkatalog mit aufzunehmen (A‑C [2]). Der wird in den nächsten Jahren realisiert. Das entlastet Books to Do. Ich muss nicht jede Arbeit hineinnehmen, sondern kann auch etwas weglassen und freier mit dem Medium umgehen. Gleichzeitig taucht in Books to Do, auch wenn das Buch keine Vollständigkeit anstrebt und keine chronologische Systematik, doch einiges auf an Themen und Arbeiten – und ist selbst ein Katalog, ein Verzeichnis von Dingen, die sich unter einem Oberbegriff fassen lassen, in dem Fall: zu machende Bücher.

AG: Die Anordnung ist nicht konsequent chronologisch, auch nicht alphabetisch, sondern eher nach Werkgruppen. Insofern hast du einen kuratorischen Blick, eine Narration, was du vielleicht auch mit dem Freiheitsgedanken verbindet: du kannst etwas weglassen, mehr zulaufenlassen auf bestimmte Stränge. Das ist aber auch eine eigene Narrativierung und Kategorisierung, eine Selbsthistorisierung deines Oeuvres. Braucht es dafür die Kunstwissenschaftler nicht mehr?

AC: Selbst innerhalb des Versuchs, ein paar Inseln deutlich werden zu lassen, ist immer noch alles ziemlich offen. Zum Beispiel: was sind das für Konstellationen, für Themen? Eine Frage war und ist die nach der Anordnung, der Gewichtung. Bei einer (digitalen) – To-do-Liste ist das Aktuellste oder das Wichtigste ganz oben – oder man rückt es nach oben. Da spiegelt sich der Zeitpunkt des Machens sich wider. Das aktuellste Projekt, die Nummer eins, ist das Buch selbst. An zweiter Stelle steht der zu produzierende Katalog bzw. die Monografie. Und dann kommen laufende Projekte, z.B. das Buch zum Denkmal für die Familie Mann. Dann sind es Ausstellungsprojekte, wo ich denke, da würde es sich lohnen ein eigenes Buch drüber zu machen. Von dieser Zeitachse geht es in Themen hinein. Aber man kann das auch anders lesen….

AG: Oben ist das Wichtigste – das leuchtet ein. Ich habe es anders gelesen: Meine To-do-Listen sind immer noch handschriftlich. Das Aktuellste kommt dazu, unten, und oben wird immer mehr ausgestrichen. Insofern würde ich nicht sofort mehr Hierarchie sehen, außer vielleicht bei der eins, das ist der Startpunkt. Ich würde nicht unbedingt sagen, was unten kommt, verliert an Aktualität. Im wissenschaftlichen Bereich oder im CV kann man mit dem aktuellsten oder mit dem ältesten beginnen. Bibliografien, Publikationslisten o.ä. fangen häufig mit eins an und enden bei 125 oder so, um zu zeigen, was für ein Riesenoeuvre besteht, da ist die höchste Zahl auch das Aktuellste. Das ist der Unterschied zwischen handschriftlicher Liste und am Computer erstellter. Und am Computer würdest du vielleicht das Erledigte löschen und nicht durchstreichen?

AC: Löschen würde ich nicht, höchstens nach unten sortieren.

AG: Zum Sortieren: Wie entscheidest du, wann etwas ein Punkt für sich ist, wann etwas nur ein Unterpunkt? Wann ist etwas Teil einer Serie, wann für sich alleinstehend? Oder wann ist es nur eine Variante ein und desselben Werks? Wo genau liegt eigentlich das Werk? Ist das die Serie? Ist es das, was da steht mit seinen Unterpunkten, oder ist es die Variante, die ich, philologisch denkend, nur tatsächlich als Variante begreifen würde?

AC: Um auf die Eingangsfrage zurückzukommen: Es geht ja um Bücher als (mögliche) Werke. Dem Medium, das mit Vervielfältigung zu tun hat, ist die Möglichkeit des Variierens eingeschrieben. Ich fand es auch im Prozess des Listenmachens reizvoll, Varianten aufzulisten, die Fragen aufwerfen. Ist z.B. die Neuauflage eines Buchs schon ein neues Buch? Ontologische Fragen stellen sich da. Ich habe auch Varianten produziert, um eine Lust am Bürokratischen hineinzubringen. Spiegelstriche, Durchstreichungen entdeckte ich als grafisches Element, und das wurde in der Heftfassung etwas Wichtiges, ein Gliederungszeichen oder auch Platzhalter für das, was noch kommt.

Jetzt haben Durchstreichungen und Striche neue Bedeutung bekommen: Das sind Trennlinien zwischen den Projekten, bilden einen Rahmen. Das ist dann auch ein Anreiz, viele Unterpunkte zu haben, um ein Raster zu schaffen.

AG: Das heißt, da, wo jetzt eine Zahl wie 1.4 ist, war in anderen Varianten der Spiegelstrich?

AC: Genau. Ich habe mich entschieden, auch die Varianten durchzunummerieren, um das Ordnen und Gliedern deutlicher in den Vordergrund treten zu lassen. Zu dieser Lust an Varianten: Ein Beispiel hast du genannt, Müde Bücher [30]. Das war ursprünglich ein Entscheidungsproblem: Gestaltet man das Cover mit einem Bild oder nur mit einer Farbfläche? Beides erschien sinnvoll. Wenn man das mit dem Bild aus dem Inhalt sieht, z.B. im Internet, weiß man sofort: aha, da geht’s um Bücher, potenzieller Kaufanreiz, für einen Verlag ist das natürlich interessanter. Die monochrome Variante bot die Möglichkeit, neutrales Material zu haben, für Installationen. Da habe ich gesagt: wir machen beides. Die Mehrkosten warnen nicht so hoch. Ich bekam 300 von der monochromen und 200 von der mit Bild und war ganz glücklich. Wenn man beide im Buchhandel präsentieren wollte, müsste man zwei Bilder einstellen.

AG: Beide haben dieselbe ISBN?

AC: Ja. Bibliographisch müssten sie unterschiedliche haben. Die monochromen Exemplare sind mehr wert, weil sie als Bestandteil von Kunstwerken im Einsatz waren, auch wieder Gebrauchsspuren haben. Das wäre eine weitere Idee, die als Edition zu präsentieren.

Cover-Varianten gab es auch bei Sacred Distancing [10]: Das Heft sollte zur Eröffnung einer Ausstellung vorliegen. Da es schnell gehen musste, ist eine erste Auflage ohne Verlag erschienen, mit einem minimalistischen Cover, auf dem nur ein Post-It zu sehen ist, etwas rätselhaft. Die zweite, aktuelle Auflage habe ich nach Rücksprache mit einem Verlag gemacht, Argobooks. Auf dem Cover erkennt man mehr, es ist zugänglicher. Nur die zweite Variante hat eine ISBN-Nummer, ist damit „offiziell“ sichtbar und im Buchhandel erhältlich.

In Schöppinger Schläger [13], einem Buch mit Tischtennisschlägern, fotografiert bei einem Stipendienaufenthalt, habe ich Texte von Mitstipendiaten, als Inlay eingebunden. Die gibt es auch als separates Heft, in kleiner Auflage. Hier sind deutscher und englischer Text gegeneinander gedreht. Varianten bieten Gelegenheit, etwas zu realisieren, was bei anderen nicht möglich war. Insofern sind das Unterpunkte der Buchprojekte.

AG: Sind sie auf jeden Fall gleichwertig? Zählt also beim letzten Beispiel dieses Inlay, wenn du es auch noch anders gestaltet hast und es anders präsentiert wird? Könnte man schon sagen, dass es ein anderes, eigenes Werk ist? Insofern musst du jedesmal, wie du vorhin sagtest, fast ontologisch eine Entscheidung treffen. Wo ziehst du eine Grenze: wo ist es eine Variante, wo tatsächlich etwas Neues, Eigenes?

AC: Da gibt es unterschiedliche Gewichtungen, was mit dem Aufwand der Produktion, aber auch mit der Wahrnehmung zusammenhängt. Man kann das auch dem Rezipienten an die Hand geben.

Es geht nicht darum, eine möglichst hohe Zahl zu erreichen mit den Unterpunkten, die man alle als Extra-Nummern deklarieren könnte. Ich wollte die Zahl der Gesamtprojekte so halten, dass sie nicht ganz unrealistisch ist. In der jetzigen Fassung sind es 96. Manche Künstler haben so viele selbständige Publikationen: In Olafur Eliassons Buch seiner Bücher, Take Your Time sind es 57, Bei Martin Kippenberger sind es laut posthumen Katalog seiner Publikationen etwa 150 (sieht im Buch nach). Es sind 149.

AG: Bei 96 – steht da nicht ein Konzept dahinter? Du hast ja auch bei 1. eine mögliche Variante mit 696 Einträgen beschrieben. Die 696 habe ich mir dann so erklärt, dass du diese Zahl beim Titel den Gesangbüchern verwendet hast.

AC: Genau. Ich finde die Zahlen Neun und Sechs interessant wegen ihrer Mehrdeutigkeit, Verdrehbarkeit und hatte schon damit gespielt, als Zitate, Nummern, die innerhalb eines Gesangbuchs auf Lieder verweisen. Weil die 100 im Raum stand: Ich war auf ein Buch gestoßen, Verschiedenes von Berengar Laurer (1972). Der skizziert 100 mögliche Bücher, also eine ähnliche Buchidee, schreibt dann: „die Zahl 100 verpflichtet aufzuhören. Alles gemacht“. 100 würde bedeuten, dass es danach nicht weitergeht, oder dass man bewusst darauf hinarbeitet würde, das wollte ich nicht. So kam es zu 96, als ein vorläufiges Ende, als der Status quo der Liste. [Nachtrag: Joachim Schmids Serie von Künstlerbüchern mit gefundenem Bildmaterial, “Other People’s Photographs” (2008–2011) erschien interessanterweise ebenfalls in 96 Bänden ]. In einer früheren Version hatte ich 75.

AG: Das war an dein Geburtsjahr gebunden.

AC: Ja, das war kein Zufall. In der ersten Version waren es übrigens 69 Nummern.

AG: Weil wir über die Varianten dieses Buches sprechen und der Liste: Was ich daran interessant finde, ist die Betonung der Varianz oder der Möglichkeiten, die in einer Idee stecken. Das zeigt, dass es schon drauf ankommt, eine Idee irgendwann zu verwirklichen, weil dann bestimmte Entscheidungen getroffen werden müssen und sich Varianten ergeben können. Das heißt, es entsteht erst beim Machen selbst, es braucht das Tun, das To do, damit das Werk entsteht.

Wie würdest du das Verhältnis zwischen Idee und Verwirklichung beschreiben, welche Bedeutung hat die Verwirklichung für dich? Hier gibt es verschiedene Sichtweisen: Lucy Lippard und Yoko Ono argumentieren, dass konzeptuelle (Ideen-)Kunst eine befreiende Wirkung habe, weil es nicht darauf ankommt, ob sie verwirklicht werden kann: „The shift of emphasis from art as product to art as idea has freed the artist from present limitations – both economic and technical. […] The artist as thinker, subjected to none of the limitations of the artist as maker, can project a visionary and Utopian art” (Lippard, vgl. Annette Gilbert: Im toten Winkel der Literatur. Grenzfälle literarischerWerkwerdung seit den 1950er Jahren, Paderborn 2018, S. 96)

Die zweite Sichtweise wäre die platonische, die davon ausgeht, dass keine Verwirklichung einer Idee je dieser vollständig entsprecht, sondern immer nur eine Annäherung darstellt – vgl. die platonische Verachtung der Materie, die auf die prinzipielle Inferiorität der Künste schließt und damit auch auf die grundsätzliche Unterlegenheit des realen Artefakts gegenüber der Idee des Werks und der Vision des Künstlers.

Und eine dritte Sichtweise (sicher gibt es noch mehr) besteht darin, die Verwirklichung einer Idee für unverzichtbar zu halten. So argumentiert z.B. John Cage, dass Kunst wesentlich auf unmittelbarer, ästhetischer Erfahrung gründe: „Obviously, if under the title ‘work of art’ I am dealing with nothing but an idea – not an experience at all – then I lose the experience. Even when I tell myself that I could have had this and that experience, if I didn’t experience it, it is lost for me!” Das wäre dann im Sinn Kenneth Goldsmiths, der postuliert: “Much conceptual writing sets out to find out what happens when a great idea is actuated into a text.” Wo siehst du dich, wie gestaltet sich für dich das Verhältnis zwischen Idee und Verwirklichung, zwischen Books-to-do und Books-that-are-done?

AC: Ich bin mehr bei der ersten Sichtweise: etwas als Idee, als Konzept formulieren zu können, das dadurch bereits Kunstcharakter hat, das empfinde ich als Möglichkeitsspielraum, als Befreiung. Das war für mich auch die Entdeckung beim Schreiben, Konzipieren der Books To-do-Liste. Vielleicht habe ich mich insgesamt von eher bildnerisch-bildhauerischen Arbeiten mehr hin zum konzeptuellen, textbezogenen bewegt. Vom Arbeitsprozess her bin ich eher, wie du sagst, beim to Do, also kein reiner Konzeptkünstler. Bei der Verwirklichung entstehen wieder neue Dinge, verändern sich, selbst wenn die Ausgangsidee formuliert ist. Das muss kein Gegensatz sein: einige Arbeiten realisiert man, andere bleiben Idee. Natürlich hat die Realisierung einen Nachteil: sie ist in ihrer Materialisierung angreifbar, bleibt eventuell hinter den Erwartungen zurück. Da wären wir bei Platon. Andererseits, wie du bemerkst: die Realisierung kann Katalysator sein für Entscheidungen, für Probleme, Lösungsversuche, neue Ideen …

AG: Ich finde das richtig, dass genau beim Punkt, der überschrieben ist mit Books to Do, so viele Varianten gelistet werden, weil es zeigt: da ist eine Idee und bei der Realisierung kommt es zu verschiedenen Entscheidungen. Das ist wie ein Manuskript in einem Nachlass, vom Philologischen ausgeht, wo man sieht: er hat das Wort durchgestrichen, ein anderes darübergeschrieben, wieder durchgestrichen, was anderes darübergeschrieben …

Diesen Prozess lässt du damit nachvollziehbar werden. Das finde ich gerade beim ersten Punkt sehr schön: 1.1 ist durchgestrichen, aber 1 nicht, im Sinne von Books to Do. Es gibt noch mehr Möglichkeiten, dieser Punkt 1 ist damit noch nicht abgeschlossen, sondern erst mal nur 1.1.

AC: Interessant. Genau da habe ich überlegt und gesagt: aus logischen Gründen müsste die 1 durchgestrichen sein, weil sie ja erledigt ist. Allerdings könnte man auch wie du sagen: solange noch eine Variante nicht gemacht ist, ist es insgesamt noch nicht erledigt.

AG: Ich fand es konsequent, dass es nicht durchgestrichen war. Wenn wir jetzt die Varianten durchgehen: Das erste Booklet mit den Spiegelstrichen ist leer geblieben auf der Cover. Beim jetzigen Entwurf ist Seite 1 das Cover?

AC: Oder das Inhaltsverzeichnis. Das ist noch offen. Grafisch finde ich das interessant, weil auch diese Durchstreichungen einen eigenen Rhythmus vorgeben.

AG: Die zwei Versionen regen völlig andere Interpretation an: Books to Do mit den Spiegelstrichen, wo es leer ist, das ist ein prospektive Entwurf, da kommt noch was. Das könnte man fast überschreiben „Books to Come“, während bei Books to Do mit den Durchstreichungen der Gedanke der To-do-Liste deutlicher ist. Das wäre dann eher etwas, was auch zurückverweist. Insofern ist es schon eine wesentliche Entscheidung, was du vorne draufmachst, ob es nur in die Zukunft verweist oder ob es beide Zeitstrahle in sich vereint.

AC: Finde ist auch nicht schlecht, wenn das Inhaltverzeichnis nicht auf dem Cover ist. Wenn man das offen lässt und nur Books to Do drauf schreibt, lässt es einen größeren Imaginationsspielraum.

AG: Das Zeit nach hinten und nach vorne Entwerfen ist zugleich Rückblick und Ausblick, wobei mir scheint, dass dem Leser nicht immer ganz klar ist, was Rückblick ist, und was vielleicht noch kommen wird. Insofern schwankt man ständig zwischen: Ist das ein Verzeichnis oder ein Arbeitsprogramm? Ich glaube, da steckt beides drin. Bei dem Ausblick bzw. Arbeitsprogramm war eine Idee, dass das dir Ansporn zu weiteren Ideen geben soll. Dabei hast du verwiesen auf das Selbstoptimierungsbuch Du kannst mehr als du denkst [Nr. 48]. Also in etwa: das ist alles möglich, das steckt alles in meiner Schaffenskraft, eine Selbstmotivation. Ich habe gewisse Vorurteile gegen diese Bücher: Man tut so, als ob man sonst wie toll drauf sei, eine Art Hochstapelei. Man könnte sagen, das passt auch wieder zu dir, diese Hochstapelei, wenn dieses Wortspiel erlaubst, weil du auch sonst wie ein Hochstapler agierst, in dem Sinne, dass du in Installationen Bücher aufeinanderstapelst und einsturzgefährdete Balancen schaffst.

Die andere Frage: inwiefern ist das tatsächlich ein Arbeitsprogramm, das du erfüllen willst und musst? Wie sklavisch wirst du dich daran halten? Es ist wahrscheinlich doch kein Ausblick. Vielleicht schon in Teilen, aber nicht im Sinne von: Du nimmst dir vor, in den nächsten zehn Jahren diese Bücher zu verwirklichen, sondern dokumentiert dein jetziges Ideenbuch, ohne damit sagen zu wollen, dass dir nicht später andere Ideen kommen, oder dass du die Hälfte davon nicht verwirklichen wirst. Insofern hat es zwar die Potentialität, aber gleichzeitig ist es eine Dokumentation deiner bisherigen Arbeit und trotz der Prospektivität mehr ein retrospektive Festhalten.

AC: Gute Assoziationen mit der Hochstapelei. Aktuell habe ich das Projekt Musterexemplar [5]. Da zeigt sich: In der Tat, ich staple, akkumuliere gerne Sachen, weil sich da Zeitlichkeit abbildet, auch plastisch-architektonisch. Dann der Aspekt, dass sich im Ausführen immer wieder neue Dinge ergeben: der Stapel der Musterexemplare war nicht geplant, sozusagen ein Nebeneffekt, ein Bonus. So etwas ergibt sich nicht, wenn man Sachen nur als Konzept festhält. Insofern ist schon die Idee, etwas zu verwirklichen und dann zu schauen, was ergibt sich daraus an neuen Varianten, die dann vielleicht wichtiger werden als die Ursprungsidee.

AG: Es ist jetzt nicht so streng konzeptuell, dass du dich sklavisch daran halten, das jetzt die nächsten Jahre abarbeiten müsstest.

AC: Nein, es ist ja gerade die Freiheit als Konzeptarbeit, das zu realisieren oder auch nicht. Es sind auch immer wieder „ungeplante“ Projekte dazugekommen, etwa Schöppinger Schläger oder Sacred Distancing, das Heft mit den Corona-Markierungen, Reaktionen auf aktuelle Phänomene und Funde. Im Unterschied zu anderen Listen fiktiver Arbeiten – z.B. Oeuvres von Eduard Levé – möchte ich schon einige verwirklichen (Wobei Levé ja auch einige ausgeführt hat).

AG: Der Leser darf jetzt rätseln, welche. Wobei du durch Durchstreichungen, Bildmaterial etc. ja markierst, welche schon ausgeführt sind.

AC: Das Durchstreichen ist eine notwenige Markierung (es ist schließlich eine To-do-Liste), aber eine immer noch vieldeutige, offene. Bei Books to Do in reiner Textform wurde ich öfters gefragt, ob das alles meine Bücher seien, also entstand auf den ersten Blick der Eindruck, dass die alle bereits realisiert sind. Der Betrachter kann auch weiterdenken. Einiges ist naheliegend, scheint als Beschreibung so klar, dass ich das gar nicht weiter ausführen brauche – so das Feedback in einigen Fällen. Etwa No Image [66], das Buch mit Bildern der Meldung, die auf dem Display bei Digitalkameras auftaucht, wenn die Speicherkarte nicht gelesen werden kann oder sonst ein Defekt vorliegt. Das kennen viele Leute. Im Titel liegt aber gerade der (paradoxe) Reiz, dass man kein Bild gezeigt bekommt. Hier das Foto des Nicht–Bildes anzuzeigen, von dem sowieso jeder weiß, wie es aussieht, wäre in Books to Do für mich zuviel, eine Doppelung gewesen. Das ist natürlich subjektiv. Bei anderen denke ich, hier lohnt es sich, reinzugehen und das weiter zu verfolgen.

AG: Darf ich eine Vermutung anstellen: Dich reizt besonders das, wo es zu verschiedenen Varianten kommen könnte. Weil du den Fall ansprichst, dass manchmal die Beschreibung reicht: Ist es auch möglich, all diese Punkte als eigene Werke zu verstehen, also Werke im Sinne von Werke, die gar nicht erst noch realisiert werden müssen? Das ist ja so wie bei Lawrence Weiners Statement wo er sagt: es ist eigentlich egal, ob das ausgeführt wird oder nicht, und auch, ob es von mir ausgeführt wird oder von jemand anderem. Wäre das etwas, wo du dich wieder finden würdest?

AC: Ja. Dass bereits eine Idee, ein Satz, Kunst sein kann – das finde ich großartig. Anfangs habe ich nicht unbedingt gleich den Bezugsrahmen der Konzeptkunst gesehen, aber als der klar wurde, war es für mich eine schöne Entdeckung! Manchmal frage ich mich, ob ich den Ansprüchen der Konzeptkunst genüge, z.B. bei der Durchführung. SoLewitt z.B. schreibt, der Künstler dürfe nicht abgehen von seinem Konzept, sondern müsse es, ohne groß nachzudenken, konsequent durchziehen. Denn es kommt nicht auf die physische Form an. Wenn der Künstler davon abgeht, ist es eine andere Arbeit. Ich weiche tatsächlich manchmal ab von der ursprünglichen Idee, so dass dann eine andere Arbeit entsteht – oder eine Variante.

AG: Man kann andere kunsthistorische Bezugspunkte nehmen, um das ein bisschen mehr abzugrenzen: Ein Beispiel ist Yoko Ono mit ihren Instruktionen, dann Bruce McLean mit King for a Day 1972 and 999 other pieces/works/things etc., eine Aufzählung von möglichen Arbeiten, in Buchform. McLeans Buch war Katalog zu einer Retrospektive in der Tate, die nur einen Tag lief (daher der Titel King for a day). Es enthält die Titel bzw. Beschreibungen von 1.000 durchnummerierten pieces / works / things verschiedenster Couleur, die häufig den Kunst- und Literaturbetrieb verspotten:

277. The immaculate conception piece. […]

589. Anti pompous crap poem reading piece.

590. Anti, anti piece.

591. Anti, anti, anti piece.

592. Cliche, cliche, cliche, cliche, cliche, cliche, cliche, piece. […]

727. .….….….….….….….….….….….…..piece.

728. .….….….….….….….….….….….…..piece.

729. .….….….….….….….….….….….…..piece.

730. dot dot dot dot dot dot dot dot dot dot dot dot piece

Das kann man – ähnlich wie Yoko Onos Grapefruit-Pieces – fast schon als Literatur/Gedicht lesen. Ist dir auch in den Sinn gekommen, nur die Titel deiner Werke (und vielleicht Metadaten etc.) anzuführen, so dass man sie wie einen fortlaufenden literarischen Text lesen kann? Und warum hast du dann entschieden, doch Bildmaterial etc. einzufügen? Das könnte man wunderbar in die Tradition fiktiver Bücherlisten und ‑kataloge einreihen, etwa die Bücherliste […] über die schönen Bücher in der Bibliothek von Saint-Victor in Francois Rabelais’ Pantagruel (1532), die Johann Fischart in Catalogus Catalogorum perpetuo durabilis (1590) weiter ausschmückte, bis hin zu vollständigen Bibliographien wie in Hartwig Rademachers Akute Literatur (2003).

AC: Die Liste als reinen Text gibt es ja bereits, in den Varianten von Books to Do, als Hefte, und als Wandarbeit. Wenn man es noch weiter auf die Titel reduzieren will, dann ist das Inhaltsverzeichnis von Books to Do (1.1) genau das. Ja, in der Tradition fiktiver Bücherlisten kann man das durchaus sehen. Selbst die Durchstreichungen sind ja kein „Beweis“ dafür, dass die Bücher tatsächlich existieren oder lassen nur bedingt Rückschluss darauf zu, in welcher Form. Bilder und Texte habe ich als Weiterentwicklung eingefügt, als Materialsammlung, und um den dokumentarisch-ernsthaften Charakter zu unterstreichen.

AG: Die Bücher von Bruce McLean und vor allem Yoko Ono wenden sich mehr an den Leser, im Sinne von Instruktionen zum Tun. Also Books to Do nicht als Anregung für dich, sondern für den Leser, und dieser Aufforderungscharakter fehlt bei dir. Bei Yoko Ono sind es Verben: tue dies oder jenes. Das hast du gar nicht, sondern wenn du deine Bücher präsentiert, sind das eher bibliografische Metadaten, die du einbringst, aber nicht: mache ein Buch mit dem Titel Books to Do. Ist also nicht intendiert, dass der Leser selbst die Idee ergreift und verwirklicht?

AC: Das ist eine persönlich gefärbte To-Do-Liste, nicht unbedingt partizipativ. Wobei ich bei vielen Ideen gedacht habe: das ist naheliegend, vielleicht hat das schon jemand gemacht. Sobald die Idee in der Welt ist, können sie theoretisch auch andere realisieren. Das wiederum ist, glaube ich, der Grund, warum es nicht so viel von diesen veröffentlichten Arbeitslisten gibt, z.B. Timm Ulrichs hat auch Notizbücher voller Ideen. Aber der veröffentlicht die nicht, weil er sich denkt: dann kommt jemand anders und realisiert das.

AG: Wie wäre das bei dir, wenn da jemand kommen und jetzt Nummer 35 machen würde, könntest du dann sagen: Moment mal, das war meine Idee?

AC: Ich würde kein Copyright reklamieren. Wenn es jemand machen würde, dann wäre es auf jeden Fall etwas anderes. Bei ähnlichen Ideen sind Ergebnisse erstaunlich unterschiedlich. Und vielleicht ist die andere Umsetzung so, dass man es nicht selbst zu machen braucht? Ein Beispiel: Ich hatte die Idee zu einem Buch mit Fotos von Geldautomaten, in Israel, Deutschland, z.B. in Berlin, etc. Habe also eine Fotosammlung angefangen und gedacht, eine schöne Buchidee – aber auch naheliegend, im öffentlichen Raum. Tatsächlich gehe ich vor paar Wochen zu Motto in Berlin und sehe da ein Buch: Berlin Cash — Geldautomaten. Ich war einerseits enttäuscht: Mein Gott, jetzt hast du zu lange gewartet mit der Umsetzung. Andererseits: das brauche ich nicht unbedingt mehr machen. Das entlastet mich. Und falls ich es doch noch eines Tages machen will, dann wird es mit Sicherheit anders.

AG: Damit hast du ein gutes Gegenargument dazu gebracht, dass es etliche Ideen in deiner Sammlung gibt, die du gar nicht verwirklichen brauchst, weil man sie sich gut vorstellen kann. Da würde ich sagen: Jede Ausführung einer Idee wird anders aussehen. Das erinnert mich an den Text von Markus Krajewski, der den Ratschlag gibt, dass man bestimmte Sachen ad acta legen sollte, wenn man entdeckt, dass jemand anders sich schon damit beschäftigt hat. In diesem Sinne würdest du Krajewski nicht folgen wollen und sagen: damit lege ich es noch lange nicht ad acta, sondern jetzt vielleicht erst recht? Die Herausforderung ist, es anders zu machen, noch eine eigene Note hineinzubringen?

AC: Das muss man Fall zu Fall entscheiden. Es gibt vieles bereits, aber manchmal ist es auch erstaunlich, was es alles noch nicht gibt, oder was man noch mal machen kann, aber etwas anders. Bereits bearbeitete Ideen können eine Entlastung sein – da würde ich Krajewski zustimmen. Es ist schon wichtig, Ausschlussmechanismen zu entwickeln.

AG: Wobei es vielleicht noch eine Ähnlichkeit gibt. Er entwickelt ja auch die These: man kann sich auch von Projekten trennen, wenn man anfängt, sie zu verwirklichen, wenn es also, mit einem Begriff aus der Rhetorik, zur dispositio kommt. Insofern gibt es da etliche Parallelen, auch wenn es sich auf zu zuschreibende Bücher bezieht, ist das durchaus auch übertragbar auf deinen Arbeitsprozess.

AC: Tatsächlich, manche Projekte bleiben an irgendeinem Punkt stecken oder es stellt sich heraus: es wird nicht so toll.

AG: Nachdem ich den Text von Krajewski gelesen hatte, habe ich mit einem anderen Blick auf deine Liste geschaut, vor allem auf die Durchstreichungen. Das muss nicht unbedingt heißen: das ist erledigt, das ist verwirklicht, sondern es könnte auch heißen: das ist verworfen.

AC: Interessant, diese doppelte Semantik von Durchstreichen! Die erste wäre bei einer To-do-Liste, dass ich es erledigt habe. Die zweite: es hat sich erledigt, passivisch, ohne mein Zutun. Man könnte die Liste verlängern, ein Buch machen von Buchideen, die schon jemand anders realisiert hat. Z.B. dieses Bancomat-Buch. Oder auch das Buch mit Fotos von Museumswärtern (custodie).

AG: Noch eine Interpretation der Durchstreichungen: ich habe gezählt, wie viele von dir durchgestrichen sind, und bin auf 19 von 96 gekommen. Nicht gerade eine hohe Zahl, nicht mal die Hälfte. Man könnte das auch negativ auslegen: Woran liegt es, dass du so vieles bisher nicht realisiert hast? Ist kein Geld da, lässt es sich nicht durchführen oder fehlt hier die Schaffenskraft? Bist du als Künstler gescheitert? Sozusagen: Ich hatte mal so und so viel vor, bin jetzt schon so und so alt, habe jetzt aber von den 100 Punkten nur 20 vorzuweisen.

AC: Die Zahl der nicht durchgestrichenen, also nicht realisierten Projekte sollte wesentlich größer sein als die der realisierten, der zukunftsgerichtete, utopische Charakter im Vordergrund stehen. Darum war es mir wichtig, dass da eine Kluft entsteht. Die auch das Normale in einem Arbeitsprozess ist, auf To-Do-Listen. Da bleibt immer etwas unerledigt stehen, dann kommt wieder etwas Neues, man kommt nicht dazu, das abzuarbeiten.

AG: Mir fällt Stephan Mallarmé ein, mit Le Livre, das große Buch, an dem er den Rest seines Lebens gearbeitet hat und das nicht zur Vollendung gekommen ist. Man könnte das schon als das Scheitern des Künstlers interpretieren.

AC: Das wäre dann so ähnlich wie bei Du kannst mehr als du denkst [48], wo ich in der Film-Version am Reck hänge und Klimmzüge versuche. Ich hatte schon an die sechs Takes gemacht, war so erschöpft, dass ich kaum einen zustande gebracht habe. Aber diese Erschöpfung war auch gut, diese Überforderung. Eine lustvolle Überforderung. Wo man sagt: so what? Ich versuche es – auch wenn ich es nicht schaffe.

AG: In Ratgebern zum Zeitmanagement taucht auch immer der Hinweis auf, man solle nicht allgemeine Punkte aufschreiben, sondern das Ganz auf viele Unterpunkte verteilen, damit man dann auch mit irgendwas anfängt. Insofern folgst du dieser Logik des Selbstmanagements.

Noch zwei kleine Fragen: Wie soll der Titel deines Buches sein? Books to Do, durchgestrichen oder nicht? Wie sollte das Buch katalogisiert werden? Du hast gesagt, du bewegst dich zwischen den Genres. Mit Durchstreichung fällt du sofort wieder aus dem System raus. In Katalogen ist es ja meist nicht möglich, so etwas wie eine Durchstreichung hineinzubringen. Wie soll korrekterweise der Titel sein, wie soll ich dich zitieren?

AC: Interessante Frage. Im Buch gibt es ja beides, Books to Do als allgemeines Projekt und dann in den Varianten, die teils realisiert sind. Ich würde eher auf das Nicht-Durchgestrichene gehen. Du hattest ja gemeint, dass Books to Do eine Offenheit hat hinsichtlich der Varianten und Unterpunkte. Ich würde diese Durchstreichung vielleicht im Buch selber machen, am Anfang noch nicht durchgestrichen, dann, wenn das Buch zu Ende ist, auf der Rückseite, so, wie bei der Heft-Ausgabe. Mit dem Anfang und dem Ende verknüpft. Vielleicht wäre noch die Frage: wie markiere ich den Unterschied, zu den anderen, vorhergehenden Varianten, den Heften, die genauso heißen?

AG: Da du ja zum Anfang erzählt, dass das die To-do-Liste eher im Digitalen gedacht ist, könnte man ja auch wie im Digitalen die Version nennen 1.0, 1.1 ….

AC: Books to Do, 1.1 … Ja, ich könnte einfach die Nummerierung im Buch übernehmen!

AG: Apropos Bibliothek: man hat ja einige Möglichkeit durch den Verlag, wie der das verschlagwortet: Würdest du es gerne als Künstlerbuch oder als Monografie einsortiert haben?

AC: Eine Monografie ist es, weil es um das Werk einer Person geht. Im Zweifel eher als Künstlerbuch. Es wird eigenwertig-künstlerisch, und der Anteil, den ich als Künstler an Inhalt und Gestaltung habe, ist schon sehr groß, wenn man von der Autorschaft ausgeht. Und: Andreas Koch, Grafiker, ist ja auch Künstler!

AG: Weil wir gerade über Typografie gesprochen haben (übrigens auf dieses Buch zur Klein-und Großschreibung warte ich mit großer Spannung, also bitte, setz dich ran!). Mich erinnert die Schrift an eine, die besonders gut vom Computer erkannt wird, eine OCR-lesbare Schrift. Ich kannte sie nicht vorher.

AC: Die heißt Menlo, wurde von Apple aufgesetzt, für digitale Anwendungen. Die hat Andreas vorgeschlagen.

AG: Pass das?

AC: Anfangs habe ich auch gefremdelt, weil ich dachte, das müsste mit einer Buchschrift gesetzt sein, einer Antiqua, gut lesbar etc. Aber die Menlo wird häufig verwendet, um Listen zu machen, digitale. Diesen Einsatz für Rechnersysteme, Aufzählungen, diese spröde Anmutung fand ich ganz passend. Für die längeren Lesetexte, unserer Interview oder den Text von Markus Krajewski verwenden wir eine andere Schrift.

Das ist übrigens ein interessanter Effekt, wenn man mit einem Grafiker zusammenarbeitet und nicht alle Entscheidungen selber trifft: Der schlägt etwas vor, worauf man nicht selbst gekommen wäre.

AG: Ich weiß von Andreas Bülhoff, meinem Mitarbeiter, dass die Menlo für Texteditoren verwendet wird, als Standard. Da schreibt man Listen, programmiert oder ähnliches. Insofern passt das. Beim Listenhaften und Bürokratischen dachte ich zunächst, man könnte eine Schreibmaschinentype verwenden, für mich früher der Inbegriff von Bürokratie und Katalogisierung. Dann hast du sozusagen das digitale Pendant dazu gewählt.

AC: Noch zum Thema Typografie, Layout. Durchstreichung auch als Raster-Systeme einzusetzen, darauf kam Andreas Koch, eine sehr schöne Idee. Denn ich wäre sehr stark vom Buch ausgegangen, so dass jedes Projekt eine eigene Seite braucht. Dagegen hat er dieses Listenmäßige mit einer Horizontalität hineingebracht, da kann man auch Seiten verkleinert in eine Zeile bringen, die Liste läuft durch. Das hebt sich ab von Büchern wie dem Katalog von Kippenbergers Büchern von Uwe Koch, wo man klassisch ein Buchprojekt auf einer Doppelseite hat. Das ist eine wissenschaftliche Monografie und hat seine Berechtigung.

AG: Das finde ich auch sehr interessant, dass es sich über die Doppelseite hinweg bewegt, Man scrollt zusagen runter. Man blättert immer noch, aber im Prinzip ist das auch eine gute Verbindung zwischen dem Digitalen und Analogen.

Noch eine letzte Frage: Du hast Markus Krajewski eingeladen, und er hat einen Text über ungeschriebenen Büchern verfasst. Das ist vielleicht das erste, was man von Büchern erwartet oder mit ihnen verbindet: Wissen, Text, weniger Bild. Auch bei den Büchern von Yoko Ono oder Lawrence Weiner gab es immer wieder Diskussionen: sind das Künstlerbücher? Oder eigentlich Gedichtbände? Übertragen auf deine Praxis, die eben nicht nur Schreiben umfasst: Sind einige deiner Bücher Literatur?

AC: Das kommt auf den Literaturbegriff an. Bei meinen Künstlerbüchern würde ich das eher verneinen. Aber da viele mit Sprache und Text arbeiten, mit Fundstücken aus der Literatur, gibt es Grenzfälle: Z.B. Englisch-Wörter, 1990/2020 [16], Reproduktion einer Wörterliste, vor 30 Jahren angelegt in der Schule. Der Anfang:

ocean

following

reach

Asia

claim

Das könnte ein minimalistisches Gedicht sein, oder eine dadaistische Wortabfolge. Wobei es eine fotografierte Liste ist; es sind nicht nur Wörter, sondern gleichzeitig auch Bilder.

AG: Könnte man sagen, in dem Moment, wo du das in Buchform präsentierst, liegt es nahe, dass man es als Literatur liest?

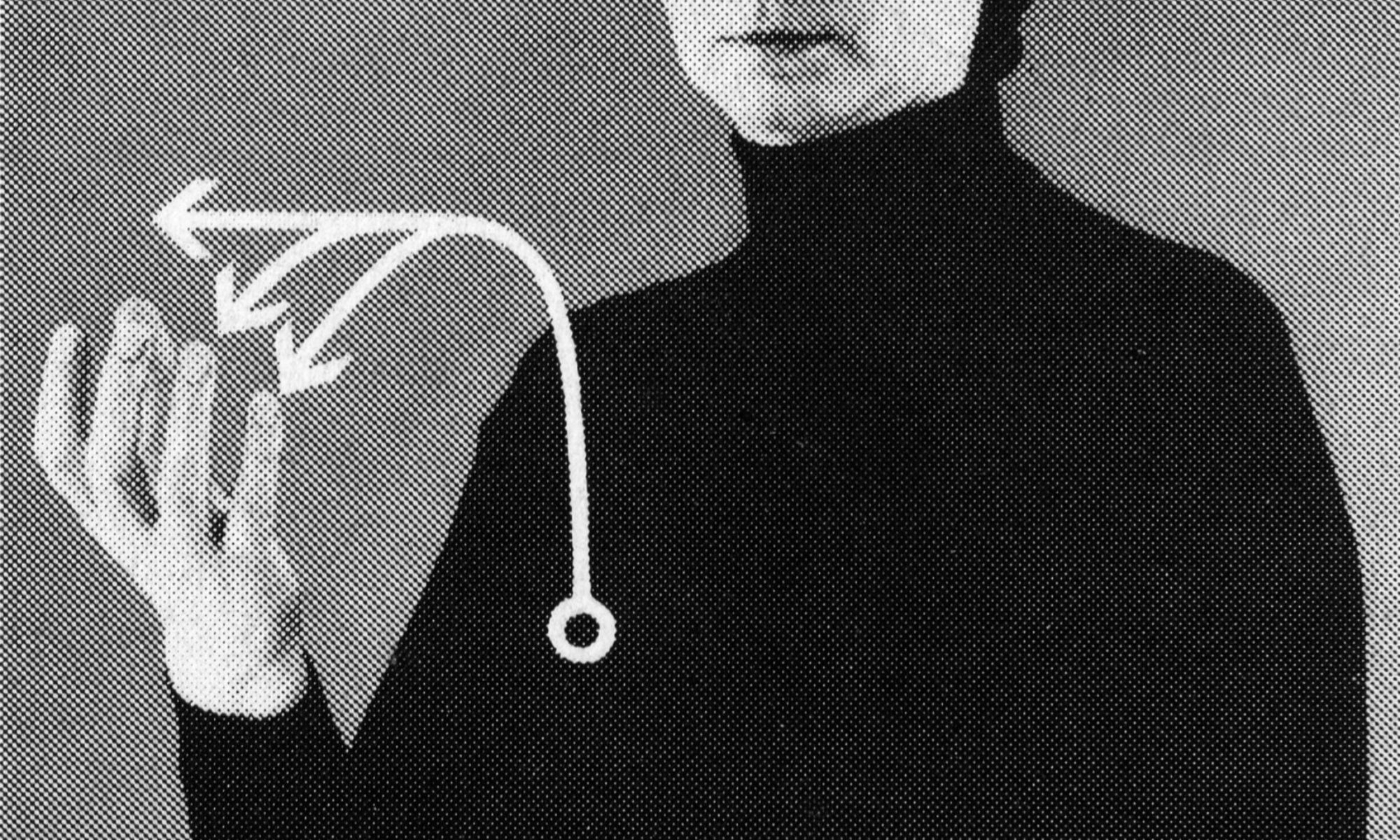

AC: Die Form beeinflusst die Rezeption, aber auch der Kontext. Mir gefallen Bücher, die Kategorisierungen in Frage stellen. Schöppinger Schläger ist ein Fotobuch, aber mit dem Inlay der Texte auch Literatur, verfasst von Leuten, die ein Stipendium für Literatur hatten – allerdings auch solchen mit einem für bildende Kunst. Oder die Bücher mit Wörtern der Gebärdensprache. Das könnte man auch als eine Form visueller Poesie sehen.

Häufig schreibe ich Texte, verfasse damit (Gebrauchs)literatur. Dann sind da die Bücher, die ich herausgegeben habe, z.B. Arbeit an der Pause, eine hybride Form von Ausstellungskatalog, Künstlerbuch und Essayband, wo ich auch Texte beigesteuert habe.

AG: Die alten Konzeptkünstler wie Lawrence Weiner z.B. haben ja immer gesagt: das ist auf keinen Fall Literatur oder Poesie, damit fühlen sie sich völlig missverstanden.

AC: Vielleicht ist diese Zeit der prononcierten Abgrenzungen vorüber? Literatur war als Begriff im Kunstbereich oft negativ konnotiert: das ist zu literarisch, zu erzählerisch. Die Reserve der Konzeptkünstler ist verständlich: Man positioniert sich im Feld der (bildenden) Kunst; dort beruht die Besonderheit eben auf der Verwendung von Texten als Träger von Ideen. Ich selbst würde es auch nicht als „Literatur“ labeln wollen. Die Zuordnung geschieht durch den Bereich, in dem es zirkuliert und rezipiert wird. Das ist bei mir überwiegend in der visuellen Kunst. In dem Zusammenhang ein Beispiel, auf das ich dank dir gekommen bin: Eduard Levé. Der hat es geschafft, mit dem Buch Oeuvres sich (auch) im Bereich Literatur zu verorten, obwohl es um fiktive Werke der bildenden Kunst geht, die er beschreibt, also Konzeptkunst ist. Er wird als Schriftsteller und Künstler bezeichnet.

AG: Dafür hat er aber lange kämpfen müssen. Das ist reiner Text, und insofern nicht mit dem Katalog, den du jetzt machst, zu vergleichen. Aber andere Bücher von dir bewegen sich durchaus auf dieser Schwelle.

in: Albert Coers: Books to Do, Berlin 2022, S. 173–182

Books to Do — Works to Do. Conversation with Annette Gilbert

In April 2022, I had a conversation with the literary and media scholar Annette Gilbert about the book Books to Do, where it is also printed. The first part of the conversation can be read here:

AG: Firstly, a question about the title: “Books to Do” makes sense because it is a book that you are producing. At the same time, many of the ideas you list are not necessarily tied to the book form. In this respect: Why “Books to Do” and not “Works to Do”?

AC: With diverse media material, collections of images, photos, drawings and installations, I often think about turning it into a book. And the works often refer to books. Spinning books further, making a commentary on an existing book: that dates back to 2014, for example. Then there were books to be written following my dissertation. More and more book ideas had accumulated. In 2019, I started collecting them and writing them down as a to-do list. There was also something liberating about that. Writing things down is often an act of externalising, of distancing oneself. At the same time, the list created something new, an independent work. I liked the self-reference of turning the list back into a book containing the book projects.

AG: Which brings to mind Mallarmé’s famous saying: “Everything in the world is meant to end up in a book.” That fits your oeuvre and is consistent. Nevertheless, not everything in the title seems to work out, because you don’t just make books, you also use books for your works. In this respect, some works are Works to Do — with books, recycling, so to speak, e.g. Tired Books [No. 30], which you then turned into installations. At the same time, a self-reflection. In this respect, it’s a cycle where you perhaps can’t separate the creation of books and the use of books.

AC: You could also read the title in the sense of an activation, “Books to Do” not as books to be made, but “Books to do something with”… Yes, this multiple use or concatenation of books was an idea within the Books to Do series.

AG: You mentioned your dissertation, which clearly also inspired your thinking about this book or the retrospective project. What did you learn from your dissertation about the catalogue as a medium? What do you associate with a classic monograph, a catatalogue raisonneé? Why didn’t you choose this form now? There are already catalogues in your list, a monograph from 2002–2008 and 2008-11, so the logical step would have been: 2011 to 21! Why are you moving away from the classic model?

AC: I have seen that a catalogue can be more than just a retrospective-documentary list that describes and records what already exists as completely as possible. It can be enriched with additional text and image material to create something that contains fictional, prospective elements, something that is an artist’s book in its own right. At the same time, I am a fan of the documentary and the catalogue, the enumeration, the list. The book offers sustainability, a shelf life that one hopes will be as long as possible. One attempt at a solution is to include a classic catalogue raisonné in the list of books still to be made ( AC [2]). This will be realised in the next few years. That will take the pressure off Books to Do. I don’t have to include every work, but can also leave something out and work more freely with the medium. At the same time, even if the book does not aim to be complete or chronologically systematic, a number of topics and works appear in Books to Do — and is itself a catalogue, a list of things that can be subsumed under a generic term, in this case: books to be made.

AG: The arrangement is not consistently chronological, nor alphabetical, but rather according to groups of works. In this respect, you have a curatorial view, a narrative, which you perhaps also associate with the idea of freedom: you can leave something out, let more run towards certain strands. But this is also your own narrative and categorisation, a self-historicisation of your oeuvre. Do you no longer need art historians for this?

AC: Even within the attempt to make a few islands clear, everything is still pretty open. For example: what are the constellations, the themes? One question was and is about the order, the weighting. In a (digital) to-do list, the most current or the most important is at the top — or you move it to the top. This reflects the point in time at which something is done. The most current project, number one, is the book itself. In second place is the catalogue or monograph to be produced. And then there are ongoing projects, e.g. the book on the memorial for the Mann family. Then there are exhibition projects where I think it would be worth making a separate book about them. It goes from this timeline into topics. But you can also read it differently …

AG: Above is the most important thing — that makes sense. I read it differently: My to-do lists are still handwritten. The most current items are added at the bottom and more and more are crossed out at the top. In this respect, I wouldn’t immediately see more hierarchy, except perhaps at one, which is the starting point. I wouldn’t necessarily say that what comes at the bottom loses its topicality. In the academic field or in the CV, you can start with the most recent or the oldest. Bibliographies, publication lists etc. often start with one and end with 125 or so to show what a huge oeuvre there is, so the highest number is also the most up-to-date. That’s the difference between a handwritten list and one created on a computer. And on the computer, perhaps you would delete the completed items and not cross them out?

AC: I wouldn’t delete them, at most I would sort them downwards.

AG: About sorting: How do you decide when something is a point in itself, when something is just a sub-point? When is something part of a series, when does it stand alone? Or when is it just a variant of the same work? Where exactly is the work? Is it the series? Is it what is there with its sub-items, or is it the variant that I, thinking philologically, would only really understand as a variant?

AC: To come back to the initial question: We are talking about books as (possible) works. The possibility of variation is inscribed in the medium that has to do with reproduction. In the process of making the list, I also found it appealing to list variants that raise questions. For example, is a new edition of a book already a new book? This raises ontological questions. I have also produced variants in order to introduce a sense of bureaucracy. I discovered indents and strikethroughs as a graphic element, and this became something important in the booklet version, a structuring symbol or placeholder for what was yet to come.

Now strikethroughs and dashes have taken on a new meaning: They are dividing lines between the projects and form a framework. This is also an incentive to have many sub-items in order to create a grid.

AG: So where there is now a number like 1.4, there was an indent in other variants?

AC: Exactly. I also decided to number the variants in order to bring the organising and structuring more clearly to the fore. About this desire for variants: You mentioned one example, Tired Books [30]. This was originally a decision problem: should the cover be designed with an image or just a colour area? Both seemed to make sense. When you see the image from the content, e.g. on the Internet, you know immediately: aha, it’s about books, a potential incentive to buy, which is of course more interesting for a publisher. The monochrome version offered the opportunity to have neutral material for installations. So I said: we’ll do both. The additional costs were not that high. I got 300 of the monochrome and 200 of the one with the picture and was quite happy. If you wanted to present both in bookshops, you would have to put two pictures in.

AG: Both have the same ISBN?

AC: Yes. Bibliographically, they should have different ones. The monochrome copies are worth more because they were used as part of artworks and have traces of use. That would be another idea, to present them as an edition.

There were also cover variants for Sacred Distancing [10]: The booklet was intended for the opening of an exhibition. As things had to be done quickly, a first edition was published without a publisher, with a minimalist cover featuring just a Post-It, which was somewhat puzzling. I made the second, current edition after consulting a publisher, Argobooks. You can recognise more on the cover, it’s more accessible. Only the second version has an ISBN number, so it is “officially” visible and available in bookshops.

In Schöppinger Schläger [13], a book with table tennis bats, photographed during a scholarship stay, I have included texts by fellow scholarship holders as an inlay. These are also available as a separate booklet, in a small edition. Here, the German and English texts are reversed. Variants offer the opportunity to realise something that was not possible with others. In this respect, these are sub-items of the book projects.

AG: Are they equivalent in any case? In the last example, does this inlay count if you have also designed it differently and it is presented differently? Could it be said that it is a different, separate work? In this respect, as you said earlier, you have to make an almost ontological decision each time. Where do you draw the line: where is it a variation, where is it really something new and original?

AC: There are different weightings, which has to do with the effort involved in production, but also with perception. You can also give that to the recipient.

It’s not about achieving the highest possible number with the sub-items, which could all be declared as extra numbers. I wanted to keep the number of total projects so that it is not completely unrealistic. In the current version, there are 96. Some artists have so many independent publications: In Olafur Eliasson’s book of his books, Take Your Time there are 57, With Martin Kippenberger, according to the posthumous catalogue of his publications, there are about 150 (check the book). There are 149.

AG: At 96 — isn’t there a concept behind it? You also described a possible variant with 696 entries in 1. I then explained the 696 in such a way that you used this number in the title of the hymnals.

AC: Exactly. I find the numbers nine and six interesting because of their ambiguity, their twistability and had already played with them as quotations, numbers that refer to songs within a hymnal. Because the 100 was in the room: I had come across a book, Miscellaneous by Berengar Laurer (1972). He outlines 100 possible books, i.e. a similar book idea, then writes: “the number 100 obliges us to stop. Everything done”. 100 would mean that it wouldn’t go on after that, or that one would consciously work towards it, which I didn’t want. So it came to 96, as a provisional end, as the status quo of the list. [Addendum: Joachim Schmid’s series of artist’s books with found images, “Other People’s Photographs” (2008–2011), interestingly enough, also appeared in 96 volumes]. In an earlier version I had 75.

AG: That was linked to your year of birth.

AC: Yes, that was no coincidence. Incidentally, there were 69 numbers in the first version.

AG: Because we’re talking about the variants of this book and the list: What I find interesting about it is the emphasis on the variance or the possibilities that are inherent in an idea. This shows that it is important to realise an idea at some point, because then certain decisions have to be made and variants can arise. In other words, it only comes into being during the making itself, it needs the doing, the to do, for the work to emerge.

How would you describe the relationship between idea and realisation, what significance does realisation have for you? There are different points of view here: Lucy Lippard and Yoko Ono argue that conceptual (idea) art has a liberating effect because it does not depend on whether it can be realised: “The shift of emphasis from art as product to art as idea has freed the artist from present limitations — both economic and technical. […] The artist as thinker, subjected to none of the limitations of the artist as maker, can project a visionary and Utopian art” (Lippard, cf. Annette Gilbert: Im toten Winkel der Literatur. Grenzfälle literarischerWerkwerdung seit den 1950er Jahren, Paderborn 2018, p. 96)

The second view would be the Platonic one, which assumes that no realisation of an idea ever fully corresponds to it, but is always only an approximation — cf. the Platonic contempt for matter, which concludes the fundamental inferiority of the arts and thus also the fundamental inferiority of the real artefact to the idea of the work and the artist’s vision

And a third point of view (there are certainly more) consists of considering the realisation of an idea to be indispensable.John Cage, for example, argues that art is essentially based on direct, aesthetic experience: “Obviously, if under the title ‘work of art’ I am dealing with nothing but an idea — not an experience at all — then I lose the experience. Even when I tell myself that I could have had this and that experience, if I didn’t experience it, it is lost for me!” That would be in the spirit of Kenneth Goldsmith, who postulates: “Much conceptual writing sets out to find out what happens when a great idea is actuated into a text.” Where do you see yourself, how do you see the relationship between idea and realisation, between books-to-do and books-that-are-done?

AC: I’m more in favour of the first point of view: being able to formulate something as an idea, as a concept, that already has the character of art, that’s what I see as a room for manoeuvre, as liberation. That was also the discovery for me when writing and designing the Books to-do list. Perhaps I have moved away from more artistic, sculptural work towards more conceptual, text-related work. In terms of the working process, I’m more, as you say, a to-do artist, so not a pure conceptual artist. During the realisation process, new things emerge and change, even if the initial idea has been formulated. That doesn’t have to be a contradiction: some works are realised, others remain ideas. Of course, realisation has a disadvantage: it is vulnerable in its materialisation and may fall short of expectations. That brings us back to Plato. On the other hand, as you point out, realisation can be a catalyst for decisions, for problems, attempts at solutions, new ideas …

AG: I think it’s right that so many variants are listed precisely at the point headed Books to Do, because it shows that there is an idea and different decisions are made during the realisation. It’s like a manuscript in an estate, from the philological point of view, where you can see: he crossed out the word, wrote another one over it, crossed it out again, wrote something else over it …

You make this process comprehensible. I particularly like the first point: 1.1 is crossed out, but 1 is not, in the sense of Books to Do. There are more possibilities, this point 1 is not yet completed, but only 1.1 for now.

AC: Interesting. That’s exactly what I was thinking about and said: for logical reasons, the 1 should be crossed out because it’s done. However, like you, you could also say: as long as one variant has not yet been done, it is not yet done overall.

AG: I thought it was consistent that it wasn’t crossed out. If we go through the variants now: The first booklet with the dashes remained empty on the cover. In the current design, page 1 is the cover?

AC: Or the table of contents. That’s still open. Graphically, I find it interesting because these crossings out also set their own rhythm.

AG: The two versions inspire completely different interpretations: Books to Do with the indents, where it’s blank, that’s a prospective draft, there’s still something to come. You could almost call it “Books to Come”, whereas the idea of the to-do list is clearer in Books to Do with the strikethroughs. That would be something that also refers back. In this respect, it’s an important decision what you put on the front, whether it only refers to the future or whether it combines both timelines.

AC: I don’t think it’s a bad thing if the table of contents isn’t on the cover. If you leave it open and just write Books to Do on it, it leaves more room for imagination.

AG: Designing time backwards and forwards is both looking back and looking forward, although it seems to me that the reader is not always entirely clear what is looking back and what is perhaps still to come. In this respect, one constantly wavers between: Is this a directory or a work programme? I think it’s both. With the outlook or work programme, one idea was that it should inspire you to come up with further ideas. You referred to the self-optimisation book You can do more than you think [No. 48]. In other words: it’s all possible, it’s all in my creative power, a self-motivation. I have certain prejudices against these books: you act as if you’re otherwise great, a kind of imposture. You could say that this also suits you, this imposture, if you don’t mind the pun, because you also act like an impostor in other ways, in the sense that you stack books on top of each other in installations and create balances that are in danger of collapsing.

The other question: to what extent is this actually a work programme that you want and have to fulfil? How slavishly will you stick to it? It’s probably not an outlook after all. Maybe in parts, but not in the sense of: You intend to realise these books in the next ten years, but document your current book of ideas, without wanting to say that you won’t come up with other ideas later, or that you won’t realise half of them. In this respect, it does have potential, but at the same time it is a documentation of your work to date and, despite its prospective nature, more of a retrospective record.

AC: Good associations with imposture. I currently have the project Musterexemplar [5]. It shows that I do indeed like to stack and accumulate things, because temporality is depicted there, also in terms of sculpture and architecture. Then there’s the aspect that new things always emerge in the execution: the pile of samples was not planned, a side effect, so to speak, a bonus. You don’t get something like that if you only record things as a concept. In this respect, the idea is to realise something and then see what new variants emerge from it, which then perhaps become more important than the original idea.

AG: It’s not so strictly conceptual that you have to stick to it slavishly and work through it over the next few years.

AC: No, it is precisely the freedom as a conceptual work to realise it or not. There have always been “unplanned” projects, such as Schöppinger Schläger or Sacred Distancing, the booklet with the corona markings, reactions to current phenomena and discoveries. In contrast to other lists of fictional works — e.g. oeuvres by Eduard Levé — I would like to realise some of them (although Levé also executed some).

AG: The reader can now guess which ones. Whereby you mark with strikethroughs, pictures etc. which ones have already been executed.

AC: The strikethrough is a necessary marker (it is a to-do list after all), but still an ambiguous, open one. With Books to Do in pure text form, I was often asked whether these were all my books, so at first glance I got the impression that they had all already been realised. The viewer can also think further. Some things are obvious, seem so clear as a description that I don’t need to explain them any further — that was the feedback in some cases. For example, No Image [66], the book with pictures of the message that appears on the display of digital cameras when the memory card cannot be read or is otherwise defective. Many people are familiar with this. But the (paradoxical) attraction of the title is that no picture is shown. Showing the photo of the non-image here, which everyone knows what it looks like anyway, would have been too much for me in Books to Do, a duplication. That’s subjective, of course. For others, I think it’s worth going in and following it up.

AG: May I hazard a guess: You are particularly attracted to that where there could be different variants. Because you mention the case that sometimes the description is enough: is it also possible to understand all these points as works in their own right, i.e. works in the sense of works that don’t even have to be realised? It’s like Lawrence Weiner’s statement where he says: it doesn’t really matter whether it’s realised or not, and also whether it’s realised by me or by someone else. Would that be something you would agree with?

AC: Yes. I think it’s great that even an idea, a sentence, can be art. At first I didn’t necessarily see the frame of reference of conceptual art, but when it became clear, it was a wonderful discovery for me! Sometimes I ask myself whether I fulfil the requirements of conceptual art, e.g. in terms of execution. SoLewitt, for example, writes that the artist must not stray from his concept, but must follow it through consistently without giving it much thought. Because it is not the physical form that matters. If the artist deviates from it, it is a different work. I do sometimes deviate from the original idea, so that a different work is created — or a variation.

AG: You can take other art-historical points of reference to delineate this a little more: One example is Yoko Ono with her Instructions, then Bruce McLean with King for a Day 1972 and 999 other pieces/works/things etc., an enumeration of possible works, in book form. McLean’s book was the catalogue for a retrospective at the Tate that only ran for one day (hence the title King for a day). It contains the titles or descriptions of 1,000 consecutively numbered pieces / works / things of various colours, which often mock the art and literature business:

277 The immaculate conception piece. […]

589. anti pompous crap poem reading piece.

590 Anti, anti piece.

591 Anti, anti, anti piece.

592 Cliche, cliche, cliche, cliche, cliche, cliche, cliche, piece. […]

727. .….….….….….….….….….….….…..piece.

728. .….….….….….….….….….….….…..piece.

729. .….….….….….….….….….….….…..piece.

730. dot dot dot dot dot dot dot dot dot dot piece

Like Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit Pieces, this can almost be read as literature/poetry. Did it occur to you to only include the titles of your works (and perhaps metadata etc.) so that they can be read as a continuous literary text? And why did you decide to include images etc. after all? This could be wonderfully placed in the tradition of fictional book lists and catalogues, such as the book list […] about the beautiful books in the library of Saint-Victor in Francois Rabelais’ Pantagruel (1532), which Johann Fischart further embellished in Catalogus Catalogorum perpetuo durabilis (1590), through to complete bibliographies such as in Hartwig Rademacher’s Acute Literature (2003).

AC: The list already exists as pure text, in the variants of Books to Do, as booklets, and as wall work. If you want to reduce it even further to the titles, then the table of contents of Books to Do (1.1) is exactly that. Yes, it can certainly be seen in the tradition of fictitious book lists. Even the strikethroughs are not “proof” that the books actually exist or only allow limited conclusions to be drawn about their form. I have included pictures and texts as a further development, as a collection of material, and to emphasise the documentary-serious character.

AG: The books by Bruce McLean and especially Yoko Ono are aimed more at the reader, in the sense of instructions for action. So Books to Do is not a suggestion for you, but for the reader, and this prompting character is missing in your work. Yoko Ono uses verbs: do this or that. You don’t have that at all, but when you present your books, it’s rather bibliographical metadata that you include, but not: make a book with the title Books to Do. So isn’t the intention that the reader takes the idea and realises it themselves?

AC: This is a personally coloured to-do list, not necessarily participative. However, with many ideas I thought: this is obvious, maybe someone has already done it. As soon as the idea is in the world, others can theoretically realise it. I think that’s the reason why there aren’t so many of these published work lists, e.g. Timm Ulrichs also has notebooks full of ideas. But he doesn’t publish them because he thinks: then someone else will come along and realise it.

AG: What would it be like for you if someone came along and did number 35 now, could you then say: Wait a minute, that was my idea?

AC: I wouldn’t claim copyright. If someone were to do it, it would definitely be something else. The results of similar ideas are surprisingly different. And maybe the other realisation is such that you don’t need to do it yourself? An example: I had the idea for a book with photos of ATMs, in Israel, Germany, e.g. in Berlin, etc.. So I started a photo collection and thought it would be a nice book idea — but also obvious, in a public space. I actually went to Motto in Berlin a few weeks ago and saw a book there: Berlin Cash — Geldautomaten. On the one hand, I was disappointed: My God, you’ve waited too long to realise this. On the other hand, I don’t really need to do that anymore. It takes the pressure off me. And if I do want to do it one day, it will certainly be different.

AG: You’ve made a good counter-argument to the fact that there are quite a few ideas in your collection that you don’t even need to realise because they’re easy to imagine. I would say that every realisation of an idea will look different. That reminds me of the text by Markus Krajewski, who gives the advice that you should shelve certain things when you discover that someone else has already worked on them. In this sense, you wouldn’t want to follow Krajewski’s advice and say: I’m not putting it aside just yet, but perhaps now more than ever? The challenge is to do it differently, to add your own flavour?

AC: You have to decide that on a case-by-case basis. A lot of things already exist, but sometimes it’s also amazing what doesn’t exist yet, or what you can do again but in a slightly different way. Ideas that have already been worked on can be a relief — I would agree with Krajewski on that. It is important to develop exclusion mechanisms.

AG: Although there is perhaps another similarity. He also develops the thesis that you can also separate yourself from projects when you start to realise them, i.e. when it comes to dispositio, to use a term from rhetoric. In this respect, there are quite a few parallels, even if it refers to books to be written, it is also transferable to your work process.

AC: Indeed, some projects get stuck at some point or it turns out: it’s not going to be that great.

AG: After reading Krajewski’s text, I looked at your list with a different eye, especially at the crossings out. That doesn’t necessarily mean: this is done, this has been realised, but it could also mean: this has been discarded.

AC: Interesting, this double semantics of crossing out! In a to-do list, the first would be that I’ve done it. The second: it’s done, passively, without me doing anything. You could extend the list, make a book of book ideas that someone else has already realised. For example, this ATM book. Or the book with photos of museum custodians (custodie).

AG: Another interpretation of the cross-outs: I counted how many of yours were crossed out and came up with 19 out of 96. Not exactly a high number, not even half. You could also interpret that negatively: Why is it that you haven’t realised so many things yet? Is there no money, can it not be realised or is there a lack of creative energy? Have you failed as an artist? So to speak: I once had so and so many plans, am now so and so old, but now only have 20 of the 100 points to show for it.

AC: The number of projects that have not been crossed out, i.e. not realised, should be much larger than those that have been realised, and the future-oriented, utopian character should be in the foreground. That’s why it was important to me to create a gap. Which is also normal in a work process, on to-do lists. There’s always something left undone, then something new comes along and you don’t get round to working through it.

AG: Stephan Mallarmé comes to mind, with Le Livre, the great book that he worked on for the rest of his life and never completed. You could interpret that as the failure of the artist.

AC: That would be similar to Du kannst mehr als du denkst [48], where in the film version I’m hanging on the horizontal bar and trying to do pull-ups. I had already done about six takes and was so exhausted that I barely managed to do one. But this exhaustion was also good, this excessive demand. A pleasurable overload. Where you say: so what? I’ll try — even if I don’t make it.

AG: Time management guides always say that you shouldn’t write down general points, but rather divide the whole thing up into many sub-points so that you can get started on something. In this respect, you are following this logic of self-management.

Two more small questions: What should the title of your book be? Books to Do, crossed out or not? How should the book be catalogued? You said you move between genres. If you cross out the title, you will immediately fall out of the system. In catalogues, it is usually not possible to add something like a strikethrough. What should be the correct title, how should I cite you?

AC: Interesting question. There are both in the book, Books to Do as a general project and then in the variants that are partly realised. I would rather go for the one that hasn’t been crossed out. You meant that Books to Do has an openness with regard to the variants and sub-items. I would perhaps do this crossing out in the book itself, not yet crossed out at the beginning, then, when the book is finished, on the back, as in the booklet edition. Linked to the beginning and the end. Perhaps another question would be: how do I mark the difference to the other, previous variants, the booklets with the same name?

AG: Since you said at the beginning that the to-do list is intended more for the digital world, you could also name the version 1.0, 1.1 .… as in the digital world.

AC: Books to Do, 1.1 … Yes, I could just use the numbering in the book!

AG: Speaking of the library: the publisher gives you some options as to how they categorise it: Would you like it to be categorised as an artist’s book or a monograph?

AC: It’s a monograph because it’s about the work of one person. In case of doubt, it’s more of an artist’s book. It will be artistic in its own right, and the contribution I make as an artist to the content and design is already very large, if you assume authorship. And: Andreas Koch, graphic designer, is also an artist!

AG: Because we were just talking about typography (by the way, I’m eagerly awaiting this book on lowercase and capitalisation, so please get on it!) The font reminds me of one that is particularly well recognised by the computer, an OCR-readable font. I didn’t know it before.

AC: It’s called Menlo and was set up by Apple for digital applications. Andreas suggested it.

AG: Does that fit?

AC: At first, I was also confused because I thought it should be set in a book font, an Antiqua, easy to read, etc. But Menlo is often used to make lists, digital ones. But Menlo is often used to make lists, digital lists. I found this use for computer systems, enumerations, this brittle appearance quite appropriate. We use a different font for the longer reading texts, our interview or the text by Markus Krajewski.

Incidentally, that’s an interesting effect when you work with a graphic designer and don’t make all the decisions yourself: they suggest something that you wouldn’t have thought of yourself

AG: I know from Andreas Bülhoff, my colleague, that Menlo is used as a standard for text editors. It’s used for writing lists, programming and the like. In that respect, it fits. When it came to lists and bureaucracy, I initially thought you could use a typewriter, which for me used to be the epitome of bureaucracy and cataloguing. Then you chose the digital equivalent, so to speak.

AC: On the subject of typography and layout. Andreas Koch came up with the idea of using strikethrough as a grid system, a very nice idea. Because I would have started very much from the book, so that each project needs its own page. On the other hand, he has introduced this list-like horizontal structure, where you can also reduce the size of pages into one line and the list runs through. This stands out from books like the catalogue of Kippenberger’s books by Uwe Koch, where you have a book project on a double page in the classic way. This is a scientific monograph and has its justification.

AG: I also find it very interesting that it moves across the double page, you scroll down, so to speak. You’re still scrolling, but in principle it’s also a good connection between digital and analogue.

One last question: you invited Markus Krajewski, and he has written a text about unwritten books. That is perhaps the first thing you expect or associate with books: Knowledge, text, less image. The books by Yoko Ono or Lawrence Weiner have also been the subject of repeated discussions: are they artists’ books? Or actually volumes of poetry? Applied to your practice, which is not just about writing: Are some of your books literature?

AC: That depends on the concept of literature. With my artist books, I would tend to say no. But since many work with language and text, with found objects from literature, there are borderline cases: E.g. English words, 1990/2020 [16], reproduction of a word list, created 30 years ago at school.The beginning:

ocean

following

reach

Asia

claim

This could be a minimalist poem or a Dadaist sequence of words Although it is a photographed list; it is not just words, but also pictures.

AG: Could one say that the moment you present this in book form, it is obvious that it should be read as literature?

AC: The form influences the reception, but also the context. I like books that question categorisations. Schöppinger Schläger is a photo book, but with the inlay of texts it is also literature, written by people who had a scholarship for literature — but also those with one for visual arts. Or the books with sign language words. You could also see that as a form of visual poetry.

I often write texts and use them to write (everyday) literature. Then there are the books that I have published, e.gArbeit an der Pause, a hybrid form of exhibition catalogue, artist’s book and essay collection, to which I have also contributed texts.

AG: The old conceptual artists like Lawrence Weiner, for example, always said: this is definitely not literature or poetry, which makes them feel completely misunderstood.

AC: Perhaps this time of pronounced demarcations is over? Literature as a term in the field of art often had negative connotations: it’s too literary, too narrative. The reserve of conceptual artists is understandable: they position themselves in the field of (visual) art, where the speciality is based on the use of texts as carriers of ideas. I wouldn’t want to label it as “literature” myself. The categorisation is based on the area in which it is circulated and received. For me, this is predominantly in the visual arts. In this context, here’s an example that I came across thanks to you: Eduard Levé. With his book Oeuvres, he has managed to (also) situate himself in the field of literature, although the works he describes are fictional works of visual art, i.e. conceptual art. He is described as a writer and artist.

AG: But he had to fight for a long time for that. It’s pure text, so it can’t be compared with the catalogue you’re making now. But other books of yours are definitely on this threshold.

in: Albert Coers: Books to Do, Berlin 2022, pp. 173–182