E‑Mail-Wechsel zwischen Jörg Scheller, Kunstwissenschaftler, Journalist, Musiker und Albert Coers, Mai ‑September 2020.

Lieber Albert,

wenn ein Leitmedium in die Jahre kommt, wird es zu Material. Von seiner Funktion des Vermittlers entbunden, kann es neu verarbeitet werden, neue Formen annehmen, in ungewohnte Kontexte überführt werden. Über die Avantgardekünstler des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts schrieb Peter Bürger, diese begriffen ihr Material, zum Beispiel Schnipsel des Mediums Zeitung, als „leeres Zeichen“. Dieses versuchten sie mit neuen Bedeutungen zu befüllen – ein Verfahren, das immer noch aktuell ist. In einer Arte-Dokumentation zieht Jonathan Meese Heideggers Sein und Zeit aus dem Regal und bekennt, das Buch nie gelesen zu haben. Er brauche es auch nicht zu lesen. Er fände das Buch so toll. Er küsst das Buch, streichelt das Buch. Auch hier also: Das einstige Leitmedium Buch ist nicht mehr Überbringer einer spezifischen Botschaft, sondern frei formbares Material des Künstlers. In Deiner bisherigen künstlerischen Arbeit mit Büchern sehe ich eine Weiterführung wie auch eine Abweichung von dieser – ein paradoxer Begriff! – Avantgarde-Tradition. Einerseits zweckentfremdest Du Bücher als künstlerisches Material, etwa als Bausteine für Installationen. Andererseits ist es Dir gerade nicht darum zu tun, die geschichtliche Verbindung zwischen Medium und Botschaft mit großer avantgardistischer Geste zu durchtrennen, sie radikal zu überwinden. Du schwingst Dich nicht zum Souverän über das Medium-Material auf. Vielmehr ist die ursprünglich durch das Medium zu vermittelnde Botschaft als Kon-Text weiterhin präsent; ich denke etwa an die Installation RIEGEL, 2019, in Berlin.

Lieber Jörg,

danke, dass Du mich da in den Zusammenhang der Avantgarden stellst! Angefangen habe ich ja mit Installationen im privatem Wohn- bzw. Atelier-Umfeld, mit eigenen Büchern und zunächst wenig darüber nachgedacht, was es da für Handlungsmuster, Traditionen etc. gibt. Ab einem gewissen Punkt, vielleicht, als der Eifer des Machens sich abgekühlt und ich öfter ausgestellt hatte, habe ich dann doch recherchiert, was es alles an Umgang mit dem Medium schon gab und versucht, das auch theoretisch zu reflektieren (da gibt es einen Buchbeitrag „Zweckentfremdungen des Buches“ und zu „Buchzerstörung“). Da sind etwa Aktionen von John Latham, der in den 1960er Jahren Lexika vor dem British Museum verbrennt, als Affront gegen das Bildungs-Establishment, Objekte und Installationen, wo Bücher genagelt, eingemörtelt etc. werden. Das hatte alles seine Berechtigung, vieles kommt mir aber schlecht gealtert oder auch zu platt vor. Näher sind mir da die Buchinstallationen von Peter Wüthrich oder Matej Kren. Dass man Bücher liebkost, wie es Meese tut, ist da ein neueres Phänomen, und natürlich auch ein provokantes show-off, zumal es um Heidegger geht… Dabei fällt mir ein, ich hatte vor längerer Zeit einen koreanischen Künstler kennengelernt, Ma Wen, der Bibeln Seite für Seite streichelte, küsste, sie aber auch zerriss, zerkaute …

Ja, der Kontext ist mir wichtig, sonst besteht die Gefahr der Beliebigkeit. Die Herausforderung ist, Zusammenhänge, Passungen herzustellen. Wobei der Kontext nicht nur in der Botschaft des Mediums besteht, sondern im ganzen Drumherum, dem Anlass, eine Arbeit zu machen, in der Architektur, in der Funktion der Räume, was es dort für evtl. bereits existierende Sammlungen gibt, was dort passiert etc.

Da war die Einladung von Susann Unger, Betreiberin des Kunstraumes Die Baeckerei in der Gotzkowskystraße in Berlin-Moabit eine schöne Gelegenheit. Denn hier gab es einen Raum voller Atmosphäre, die ehemalige Bäckerei Seidenschnur, bei der ich, wohnhaft zwei Häuser weiter, selbst öfters eingekauft hatte. Dann Susanns Sammlung zum Thema ‚Food’ in weiterem Sinn, Kochbücher, kulinarische Reiseführer, Lehrbücher für das Hotelier- und Gaststättengewerbe, Food-Magazine, etwa das deutsche Beef!. Das ist ja auch die Ausrichtung des Raumes, in Anknüpfung an die vorhergehende Nutzung als Bäckerei. Da haben unter anderem Erik Steinbrecher oder Thomas Rentmeister ausgestellt, die dezidiert auf das Thema Nahrung abheben. Beim mir war das bislang nicht der Fall, vielleicht, weil ich selber nicht besonders ausgiebig und erfolgreich koche (heute Mittag ist mir ein Topf Reis angebrannt). Ich dachte aber schon länger an die Möglichkeit, mit Kochbüchern zu arbeiten, etwa denen meiner Eltern (mein Vater hat meiner Mutter oft Kochbücher geschenkt, was Aufforderungscharakter hatte, mit entsprechenden Widmungen). Und hier war jetzt die Gelegenheit!

Lieber Albert,

das Thema Nahrung ist dahingehend ein amüsantes, dass Ernährungsfragen heute eine religiöse Dimension attestiert wird. Die drei großen monotheistischen Religionen sind Buchreligionen. Ihre heiligen Schriften bieten moralische Orientierung, stellen Gebote und Verbote auf, setzen nicht zuletzt Tabus. Es ist zwar keine besonders originelle These, aber vielleicht finden wir ja Spuren des religiösen Bedürfnisses nach Orientierung, Ordnung und Reinheit in heutigen für spezifische Identitätsgruppen verfassten Kochbüchern – hier eine kulinarische Ordnung für den Paleo-Adepten, hier eine kulinarische Ordnung für die Veganerin… Als Nicht-Koch müsste man Dich den Agnostikern, wenn nicht gar den Atheisten zurechnen, was wiederum ganz gut zur geläufigen These, dass das moderne Kunstsystem eine Folge der Säkularisierung wie auch der Säkularisation ist, passen würde. Anyway! Wie bist Du die Arbeit an RIEGEL angegangen?

Lieber Jörg,

Ich habe viel ausprobiert und am Ende eine Serie von Installationen entwickelt, die, das war mir diesmal wichtig, eine gewisse Leichtigkeit hatten, keine Materialschlacht waren. Ein tolles Einrichtungsstück im Raum ist die alte Ladenvitrine. Die habe ich zunächst befüllt mit Lagen von aufgeschlagenen Büchern mit leckeren Fotos, Schlachtplatten, Büffets der 50er/60er Jahre, wie Blätterteig oder Lagen von Schinken (siehe auch die Bezeichnung „Schinken“ für dicke, alte Bücher). Hier waren dann nur noch die Bilder präsent, das Essen selbst abwesend.

Das war aber immer noch zuviel, und ich habe weiter reduziert. Viele der Bücher stammten aus zweiter Hand, hatten geschriebene Preisschilder aufgeklebt. Die Bücher habe ich dann nach ihrem Preis sortiert, mit dem Cover nach oben. Das war besser, aber immer noch zuviel – und schließlich habe ich nur einige der Schildchen in die Vitrine gelegt, sozusagen als Stellvertreter der Bücher. Dadurch kam deren Warencharakter zum Tragen, denn in der Vitrine lagen zu Bäckerszeiten ja auch mit Preisen ausgezeichnete Waren aus. Die kleinen aufgerollten Klebeschildchen entwickelten ein Eigenleben, wurden zu Miniaturskulpturen, zudem so klein, dass man sie erst auf den zweiten Blick wahrnahm. Viel minimalistischer ging es kaum.

Der Namensgeber für RIEGEL aber war die Installation von quer in den Zwischenraum der Griffstange der Tür geklemmten Büchern, was ein Aufziehen der Tür von außen unmöglich machte. Das war zunächst eine spontane, einfache Geste, naheliegend. Denn der Raum sollte, das war eine Vorgabe von Susann, während der Ausstellung nicht betretbar, sondern nur durch das Schaufenster einzusehen sein. Ich hatte ja schon mehrfach Räume und Fenster mit Büchern verschlossen, und sowas war zunächst auch angedacht; ich wollte mich aber nicht wiederholen, und war ganz glücklich, als ich auf die Lösung kam. Außerdem passte „Riegel“ auch zum Food-Kontext, siehe Schoko‑, Müsli- etc. ‑riegel, und zur querliegenden Form der nach ihrem Preis sortierten Bücher am Boden …

Weiter hinten gab es eine zweite, noch einfachere Verriegelung bzw. Sperre, ein Buch, das als Keil zwischen Boden und Unterkante der rückwärtigen Tür geklemmt war, so, dass die Tür einen Spalt geöffnet war, anderseits blockiert, als Abschluss der Serie von Installationen. Das Buch war von den Dimensionen und vom Titel her bewusst gewählt: Das Wort „mühelos“ als Anfang des Buchtitels stand im Widerspruch zum Akt des Verkeilens und zur Energie, die nötig war, um die Türe zu öffnen.

Lieber Albert,

gehe ich recht in der Annahme, dass sich hinter dem Verschließen von Räumen mit Hilfe von Büchern ein Seitenhieb gegen bildungsbürgerliche Klischees verbirgt? Um Bücher wurde ja lange Zeit ein veritabler Kult im Kulturmarketing getrieben: Bücher führen uns in neue Welten, Bücher erweitern den Horizont, Bücher erschließen uns unbekannte Räume! Das ist medientheoretisch betrachtet zwar äußerst unterkomplex, ja irreführend, vermögen doch auch andere Medien dies. Aber mit dem Bürgertumsforscher Peter Gay gesprochen, haben Vorstellungen „nicht geringeren Wirklichkeitsgehalt als die nackteste Empirie“. Du hingegen verschließt nicht nur Bücher, indem Du sie ineinander verkeilst. Du verunmöglichst auch den Zugang zur Welt hinter den Büchern, lässt sie zu Mauern, Barrieren, Hindernissen werden. In diesem Zusammenhang interessiert mich Deine Auseinandersetzung mit der Tradition des Bildungsbürgertums, die sich als roter Faden durch Deine Arbeit zieht. Was war dieses alteuropäische Bildungsbürgertum, was interessiert Dich daran und welche Bedeutung hat es für unsere transkulturelle, globalisierte Gegenwart?

Lieber Jörg,

das war, vor allem in den ersten Buchinstallationen, sicher ein Aspekt, da kam aber Lust an der Zweckentfremdung, am plastischen Einsatz, an der Aktivierung von Material hinzu. Die Auseinandersetzung mit dem Buchmedium und damit implizit dem Bildungsbürgertum war die mit meinem biographischen Hintergrund. Da hätten wir das Interesse. Ich stamme ich aus einem Haushalt, den Bücher und Gedrucktes dominierten: alles voll davon, überall Regale; über den Türen, über dem Bett. Gesammelt hat das mein Vater, Kunstlehrer. Wenn es eine Personifikation des Bildungsbürgers gibt, dann ist er das. Beim Essen wurden ständig Lexika bemüht, der Brockhaus, der Meyer. Einerseits fand und finde ich das toll, anderseits war mir das Pathos dann auch wieder zuviel. Und da steckte eine pädagogische Absicht dahinter: Zum Geburtstag und zu Weihnachten gab’s einen dicken Band, das Ullstein-Lexikon der Musik z.B., den Reiners (Gedichte) oder auch den monumentalen Leonardo da Vinci von Taschen. Insofern steckt da ein Akt der Distanzierung dahinter, der Emanzipation von Ansprüchen, Erwartungen, Einflussnahme. Im Sinne von „Kill your idols“.

Was das alteuropäische Bildungsbürgertum war… „Ein weites Feld“.

Im Begriff steckt, dass Bildungswissen und Tätigkeit auf Gebieten wie Wissenschaft, Literatur, Musik, als Ausweis der Zugehörigkeit zu einer gehobenen, eben bürgerlichen Gesellschaftsschicht zählt, nicht Geburt oder materieller Besitz bzw. Einkommen. Also hätte Bildung ein emanzipatorisches Potential, siehe z.B. die Figur Anton Reiser. Dazu kommt ein spezifisch in Deutschland im 18. Jh. geprägter, auf das Subjekt orientierter Bildungsbegriff. Interessant auch, dass es für „Bildungsbürgertum“ keine so richtig passende Übersetzung gibt („educated middle class“?). Dieses emanzipatorische Potential finde ich auch in der Gegenwart beachtenswert. Weiter gefällt mir die Idee von zweckfreier, nicht unmittelbar verwertbarem Wissen und Können. Und, bezogen auf das „alteuropäisch“ (wobei man sich noch unterhalten könnte, was das heißt), die Idee, dass es da einen europäischen, transnationalen Zusammenhang gibt …

Dann gibt es aber auch eine kritische Stoßrichtung des Begriffs: „bildungsbürgerlich“ im Sinn von auf einen überkommenen Bildungskanon, eine Attitüde bezogen. Mir ist es noch im Ohr, wie Heribert Sturm, Ex-Professor an der Kunstakademie, mir einmal halb scherzhaft sagte, als ich einer Arbeit, eine Figur in einem Apothekerglas, den Titel Homunkulus gab, in Anspielung auf den Faust: „Er ist ein alter Bildungsbürger“. Der Begriff „Bildungsbürger“ selbst stammt vom Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts – als die Figur kritisch reflektiert und eher negativ besetzt wurde, was sich dann in den 60er Jahren fortsetzte. Da schwingt mit Kritik an einem normativ-exklusiven Bildungsbegriff, an mangelnder Resilienz gegenüber der NS-Ideologie, die Verschmelzung mit dem Staatstragend-Etablierten-Bourgeoisen. Mit dem Normativen verbindet sich die Vorstellung eines Habitus, des Oberlehrerhaften – siehe auch mein Vater, dessen Berufsbezeichnung tatsächlich „Fachoberlehrer“ war….

Lieber Albert,

auch eine Deiner jüngsten Arbeiten steht im Kontext des Bildungsbürgertums: Im Jahr 2018 hast Du den Wettbewerb des Kulturreferats München für ein Denkmal im öffentlichen Raum für die Familie des Schriftstellers Thomas Mann gewonnen. Wie kaum ein anderer stellt Mann eine, gleichwohl immer schon umstrittene, Referenz- und Identifikationsfigur des deutschen Bildungsbürgertums beziehungsweise seiner Restbestände dar. Mann kritisierte den NS zwar offen in Texten, Vorträgen und Radioansprachen. Im deutschen Widerstand wirkte er jedoch nicht aktiv mit, sondern emigrierte in die USA. Seine Bücher wurden von den Nazis nicht verbrannt. Beschließen wir unser Gespräch also mit dem Politischen: Tragen Künstler aus Deiner Sicht eine besondere politische Verantwortung, insofern sie sich und ihr Werk in der Öffentlichkeit exponieren? Oder könnte man im Gegenteil argumentieren, Künstler trügen eine besondere Form der Verantwortungslosigkeit, was sie implizit zum Ärgernis illiberaler Regime mache, da diese nach Kontrolle strebten und im Grunde nur „embedded artists“ akzeptierten? Angesichts der in Teilen der Welt sich abzeichnenden, populistisch-autoritären „Großen Regression“ (Heinrich Geiselberger) sind dies drängende Fragen. Weiters würde mich interessieren, was es mit der Würdigung von Elisabeth Mann und Katia Mann vermittels Deines Denkmals auf sich hat. Steht diese im Zusammenhang einer längeren Auseinandersetzung mit emanzipatorischen und feministischen Anliegen, oder wurdest Du von den aktuellen Ereignissen rund um #MeToo inspiriert?

Lieber Jörg,

Ja, genau, die Familie Mann fiel mir im Zusammenhang mit Bildungsbürgertum auch ein. Da hätten wir den Übergang von einer Kaufmannsfamilie, also Besitzbürgertum, zu einer, in der fast alle in irgendeiner Weise schreibend, musikalisch, akademisch unterwegs sind. Thomas Mann hat den Prozess sozialer Veränderung reflektiert, etwa in den Buddenbrooks, wenn auch unter negativen Vorzeichen, als Verfallsgeschichte. Wobei bei ihm selbst Bildungs- und Besitzbürgertum dann doch wieder zusammenkamen, er selbst als „notorischer Villenbesitzer“, wie ihn Brecht genannt hat. Und seine Wandlung vom National-Konservativen hin zu Sozialdemokratie und Sozialismus ist eine spannende, nicht widerspruchsfreie Geschichte. Kürzlich war ich in der Ausstellung Thomas Mann: Democracy will win! im Literaturhaus München, wo es eben um den politischen Schriftsteller Mann geht. Dabei hing auch groß das Label „Verantwortung“ als Objekt im Raum.

Ob Künstler allgemein eine besondere politische Verantwortung haben? Wie Du schreibst, lassen sich sowohl dafür Argumente finden als auch für „Verantwortungslosigkeit“. Im Zweifel wäre ich bei letzterer. Ich würde Künstlern nicht allgemein eine besondere politische Verantwortung zuweisen (im Sinn von Aufgreifen von Themen), sondern das jedem selbst überlassen, inwieweit das eine Notwendigkeit ist und sich auch aus dem Werkzusammenhang ergibt. Denn ihrer Arbeit sind Künstler primär verantwortlich. In dem Sinn hat sich auch Thomas Mann geäußert. Konkreter wird es, wenn sich Künstler für die Verbesserung der Arbeits- und Ausstellungsbedingungen einsetzten, also im weiteren Sinn kulturpolitisch tätig sind, in Berufsverbänden, Interessegemeinschaften, Vereinen. Ich denke hier z.B. an die Initiativen zum Erhalt von Atelierräumen, etwa der Uferhallen in Berlin, und da an Peter Dobroschke, der sich sehr engagiert.

Lieber Albert,

freut mich, dass Du dich eher auf der Seite der ‚Verantwortungslosen’ findest – ich bin da bei Max Frisch, der zwischen Bürger und Künstler differenzierte. Als Künstler offen, poetisch, kritisch, kontrovers, nichts und niemandem verpflichtet, als Bürger in der Verantwortung, insbesondere auch der politischen.

Lieber Jörg,

noch zur Verantwortung und zum Politischen: Mir ist in Erinnerung „Seid Sand, nicht das Öl im Getriebe der Welt“ (Günter Eich). Wenn man etwas macht, was Abläufe stört, sich nicht glatt einfügt. Das kann man politisch beziehen oder auch räumlich. „Skulptur ist das, was im Weg steht“ hat Kaspar König mal gesagt, und dabei vor allem Kunst im öffentlichen Raum gemeint – was ich schon passend finde, gerade auch im Bezug auf das Mann-Denkmal. Eine gewisse Sperrigkeit finde ich nicht schlecht.

Was die Verantwortung bei Kunst im öffentlichen Raum angeht: Dort sind Themen und Spielräume ja meist abgesteckt, man reagiert auf etwas. Da mitzumachen, sich auf etwas einzulassen, ist natürlich bereits eine „politische“ Entscheidung. Dann aber geht es um ein Austarieren zwischen Vorgaben, Erwartungen und den eigenen Interessen und Ideen, der „Verantwortung“ wenn man so will, gegenüber einem selber.

Dass auch Elisabeth Mann-Borgese und Katia mittels Straßenschilder beim Denkmal dabei sind, ist schon in der Ausschreibung angelegt, in der es nicht nur um Thomas Mann, sondern um die Familie als Ganzes gehen soll. Das stecken die von Dir angeführten Debatten natürlich drin. Und gerade in den letzten Jahren gab es einige Straßen, die man nach Frauen der Familie Mann benannt hat, etwa Erika oder Elisabeth. Der Familienname ‚Mann’ dagegen verweist paradoxerweise allein auf das männliche Geschlecht. Da spielt bei mir auch ein sprachliches Interesse für Namen und ihre Bedeutung mit hinein.

Über die „realen“ Schilder hinaus ist mein Beitrag, ein eigenes Schild für Katia anfertigen zu lassen, nach der nirgends eine Straße benannt ist. Den Blick auf die wenig beachtete „Frau Thomas Mann“ gelenkt zu haben, war das Verdienst einer Freundin; sie hat mich z.B. auf Inge und Walter Jens’ Biographie Frau Thomas Mann – das Leben der Katharina Pringsheim und auf Viola Roggenkamps Buch über Erika Mann hingewiesen – wie überhaupt Austausch und Diskussion Bestandteil der Arbeit am Denkmal ist …

Books, Bars, Educated Citizens – and the Mann Family. E‑mail Dialogue Jörg Scheller – Albert Coers, 2020

E‑mail exchange between Jörg Scheller, art historian, journalist, musician and Albert Coers, May ‑September 2020

Dear Albert,

When a leading medium is getting on in years, it becomes material. Relieved of its function as a mediator, it can be reprocessed, take on new forms, be transferred into unfamiliar contexts. Peter Bürger wrote about the avant-garde artists of the early 20th century that they understood their material, for example snippets of the newspaper medium, as an “empty sign”. They tried to fill this with new meanings – a process that is still current. In an Arte documentary, Jonathan Meese pulls Heidegger’s Being and Time from the shelf and confesses that he has never read the book. He doesn’t need to read it either. He thought the book was so great. He kisses the book, caresses the book. So here too: the former leading medium, the book, is no longer the bearer of a specific message, but the artist’s freely malleable material. In your artistic work with books so far, I see a continuation as well as a deviation from this – a paradoxical term! – avant-garde tradition. On the one hand, you misuse books as artistic material, for example as building blocks for installations. On the other hand, you are not concerned with severing the historical connection between medium and message with a grand avant-garde gesture, with radically overcoming it. You don’t set yourself up as sovereign over the medium-material. Rather, the message originally to be conveyed through the medium continues to be present as a con-text; I am thinking, for example, of the installation RIEGEL, 2019, in Berlin.

Dear Jörg,

Thank you for placing me in the context of the avant-garde! I started with installations in my private home or studio, with my own books, and at first I didn’t think much about what patterns of action, traditions etc. there were. At a certain point, when the enthusiasm for making had cooled down and I had exhibited more often, I researched all the ways in which the medium had already been used and tried to reflect on this theoretically (there is an article in the book “Zweckentfremdungen des Buches” and on “Buchzerstörung”). There are, for example, the actions of John Latham, who burned encyclopaedias in front of the British Museum in the 1960s as an affront to the educational establishment, objects and installations where books were nailed, mortared, etc. All this had its justification, but much of it seems to me to have aged badly or to be too flat. The book installations by Peter Wüthrich or Matej Kren are closer to me. Caressing books, as Meese does, is a more recent phenomenon, and of course also a provocative show-off, especially since it’s about Heidegger… It occurs to me that a long time ago I met a Korean artist, Ma Wen, who caressed Bibles page by page, kissed them, but also tore them up, chewed them …

Yes, the context is important to me, otherwise there is a danger of arbitrariness. The challenge is to create connections, fits. Whereby the context is not only the message of the medium, but the whole surrounding, the reason for making a work, the architecture, the function of the rooms, what collections might already exist there, what happens there, etc.

The invitation from Susann Unger, owner of the art space Die Baeckerei in Gotzkowskystraße in Berlin-Moabit, was a wonderful opportunity. For here there was a room full of atmosphere, the former bakery Seidenschnur, where I, living two houses away, had often shopped myself. Then there was Susann’s collection on the subject of ‘food’ in a broader sense, cookbooks, culinary travel guides, textbooks for the hotel and restaurant trade, food magazines, such as the German Beef! That is also the orientation of the space, in connection with its previous use as a bakery. Erik Steinbrecher and Thomas Rentmeister, among others, have exhibited there, focusing on the theme of food. This hasn’t been the case for me so far, perhaps because I don’t cook very extensively or successfully myself (I burnt a pot of rice at lunch today). But I’ve been thinking for a while about the possibility of working with cookbooks, for example those of my parents (my father often gave my mother cookbooks, which had a challenging character, with appropriate dedications). And now here was the opportunity!

Dear Albert,

The topic of food is an amusing one in that nutritional issues are nowadays seen as having a religious dimension. The three great monotheistic religions are book religions. Their holy scriptures offer moral orientation, set commandments and prohibitions, and, not least, set taboos. It’s not a particularly original thesis, but perhaps we can find traces of the religious need for orientation, order and purity in today’s cookbooks written for specific identity groups – here a culinary order for the Paleo adept, here a culinary order for the vegan… As a non-cook, you would have to be counted among the agnostics, if not the atheists, which in turn would fit quite well with the common thesis that the modern art system is a consequence of secularising as well as secularisation. Anyway! How did you approach the work on RIEGEL?

Dear Jörg,

I tried out a lot and ended up with a series of installations that, this time it was important to me, had certain lightness, were not a battle of materials. A great piece of furniture in the room is the old shop showcase. I first filled it with layers of opened books with delicious photos, butcher’s plates, buffets of the 50s/60s, like puff pastry or layers of ham (see also the term “ham” for thick, old books). Here, then, only the pictures were present, the food itself absent.

But that was still too much, and I reduced further. Many of the books were second-hand, had written price tags stuck on them. I then sorted them according to price – and put some labels in the showcase, as a proxy for the books, so to speak. In this way, the character of the goods came to the fore, because in the baker’s time, goods with prices were also displayed in the showcase. The small rolled-up adhesive labels took on a life of their own, becoming miniature sculptures, so small that they were only noticed at second glance. It could hardly be much more minimalist.

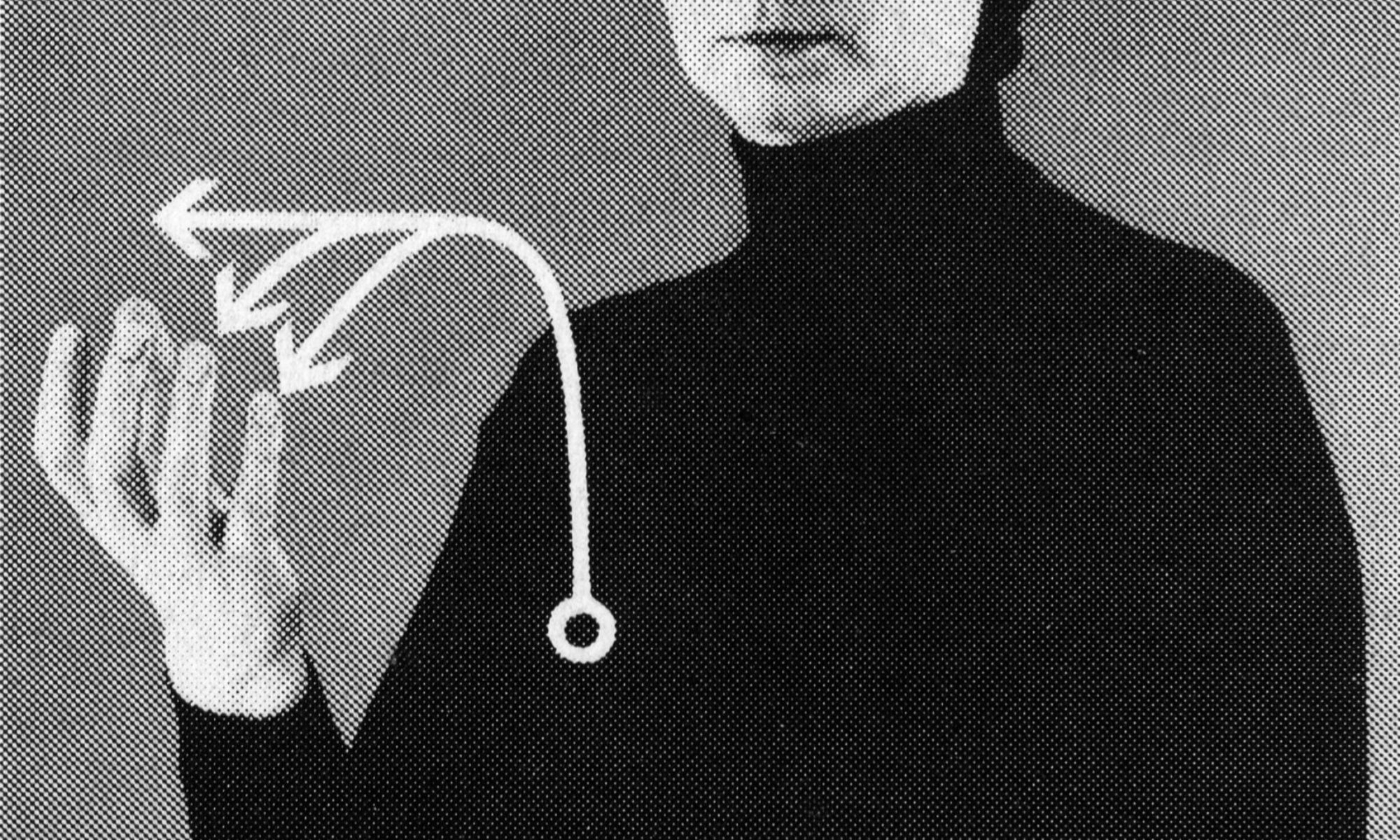

The eponym for RIEGEL, however, was the installation of books clamped crosswise in the space between the door handles, which made it impossible to pull the door open from the outside. At first, this was a spontaneous, simple gesture, obvious. Susann had specified that the room should not be accessible during the exhibition, but only visible through the shop window. I had already closed off rooms and windows with books several times, and something like that was also initially planned; but I didn’t want to repeat myself, and was quite happy when I came up with the solution. Besides, “bar” also fitted the food context, see chocolate bars, muesli bars, etc., and the transverse form. ‑bars, and to the transverse shape of the books sorted by price at the bottom …

Further back, there was a second, even simpler lock, a book that was wedged between the floor and the lower edge of the rear door, so that the door was open a crack, blocked on the other side, as the end of the series of installations. The book was deliberately chosen in terms of dimensions and title: The word “effortless” as the beginning of the book’s title was in contradiction to the act of wedging and the energy needed to open the door.

Dear Albert,

Am I right in assuming that the closing of rooms with the help of books is a side blow against educated bourgeois clichés? For a long time, books were the subject of a veritable cult in cultural marketing: Books lead us into new worlds, books broaden our horizons, books open up unknown spaces! From a media-theoretical point of view, this is extremely under-complex, even misleading, since other media can also do this. But in the words of the bourgeoisie researcher Peter Gay, ideas have “no less reality content than the most naked empiricism”. You, on the other hand, not only close books by wedging them together. You also make access to the world behind the books impossible, let them become walls, barriers, obstacles. In this context, I am interested in your examination of the tradition of the educated middle class, which is a common thread running through your work. What was this old European educated middle class, what interests you about it and what significance does it have for our transcultural, globalized present?

Dear Jörg,

that was certainly an aspect, especially in the first book installations, but there was also a desire for the alienation of purpose, for the plastic use, for the activation of material. The confrontation with the book medium and thus implicitly with the educated middle class was the one with my biographical background. There we have the interest. I come from a household dominated by books and printed matter: everything full of them, shelves everywhere; above the doors, above the bed. My father, an art teacher, collected them. If there is a personification of the educated citizen, it is him. Encyclopaedias were constantly used at meals, the Brockhaus, the Meyer. On the one hand, I thought that was great, and still do, but on the other hand, the pathos was too much for me. And there was a pedagogical intention behind it: For my birthday and at Christmas I got a thick volume, the Ullstein Encyclopaedia of Music, for example, or the Reiners (poems) or the monumental Leonardo da Vinci by Taschen publisher. In this respect, there is an act of distancing behind it, of emancipation from claims, expectations, influence. In the sense of “Kill your idols”.

What the old European educated bourgeoisie was… “A broad field”.

The term implies that educational knowledge and activity in fields such as science, literature and music count as proof of belonging to an upper, or bourgeois, social class, not birth or material possessions or income. So education would have an emancipatory potential, see for example the figure of Anton Reiser. In addition, there is a concept of education that was specifically coined in Germany in the 18th century and is oriented towards the subject. It is also interesting that there is no suitable translation for “educated middle class” (“educated middle class”?). I find this emancipatory potential worthy of attention even in the present. I also like the idea of knowledge and skills that are free of purpose and not directly usable. And, referring to the “old European” (although one could still discuss what that means), the idea that there is a European, transnational context …

But then there is also a critical thrust of the term: “Bildungsbürgerlich” in the sense of referring to an outdated educational canon, an attitude. I still remember how Heribert Sturm, ex-professor at the Art Academy, once told me half-jokingly when I gave a work, a figure in an apothecary’s jar, the title Homunculus, alluding to Faust: “He’s an old educated bourgeois”. The term “Bildungsbürger” itself comes from the beginning of the 20th century – when the figure was critically reflected and rather negatively connoted, which then continued in the 1960s. It resonates with criticism of a normative-exclusive concept of education, of a lack of resilience to Nazi ideology, the conflation with the state-supporting-established-bourgeois. The normative is associated with the idea of a habitus, of being a senior teacher – see also my father, whose job title was in fact “Fachoberlehrer” (senior teacher).…

Dear Albert,

One of your most recent works is also in the context of the educated middle class: in 2018, you won the competition of the Munich Department of Culture for a monument in public space for the family of the writer Thomas Mann. Like hardly anyone else, Mann represents a figure of reference and identification of the German educated middle class or its remnants, which has nevertheless always been controversial. Mann openly criticised the Nazis in texts, lectures and radio addresses. However, he did not actively participate in the German resistance, but emigrated to the USA. His books were not burned by the Nazis. So let’s conclude our conversation with the political: In your view, do artists bear a special political responsibility insofar as they expose themselves and their work to the public? Or could one argue, on the contrary, that artists bear a special form of irresponsibility, which implicitly makes them the nuisance of illiberal regimes, since these strive for control and basically only accept “embedded artists”? In view of the populist-authoritarian “Great Regression” (Heinrich Geiselberger) emerging in parts of the world, these are pressing questions. I would also be interested to know what the tribute to Elisabeth Mann and Katia Mann by means of your monument is all about. Is this in the context of a longer engagement with emancipatory and feminist concerns, or were you inspired by the current events surrounding #MeToo?

Dear Jörg,

Yes, exactly, the Mann family also came to mind in connection with the educated middle class. There we have the transition from a merchant family, i.e. a propertied bourgeoisie, to one in which almost everyone is active in some way in writing, music or academia. Thomas Mann reflected the process of social change, for example in Buddenbrooks, albeit under negative auspices, as a story of decay. In his case, however, the educated and the propertied middle classes came together again, he himself as a “notorious villa owner”, as Brecht called him. And his transformation from national conservative to social democracy and socialism is an exciting story, not without contradictions. I recently visited the exhibition Thomas Mann: Democracy will win! at the Literaturhaus in Munich, which is all about the political writer Mann. The label “responsibility” was also hanging large in the room as an object.

Do artists in general have a special political responsibility? As you write, arguments can be found for this as well as for “irresponsibility”. In case of doubt, I would go with the latter. I would not assign artists a special political responsibility in general (in the sense of taking up issues), but leave it up to each individual to decide to what extent this is a necessity and also arises from the context of the work. For artists are primarily responsible for their work. Thomas Mann also expressed himself in this sense. It becomes more concrete when artists campaign for the improvement of working and exhibition conditions, i.e. when they are active in cultural politics in a broader sense, in professional associations, interest groups, societies. I am thinking here, for example, of the initiatives to preserve studio space, such as the Uferhallen in Berlin, and here of Peter Dobroschke, who is very committed.

Dear Albert,

I’m glad you find yourself more on the side of the ‘irresponsible’ – I’m with Max Frisch, who differentiated between citizen and artist. As an artist, open, poetic, critical, controversial, committed to nothing and no one; as a citizen, responsible, especially politically.

Dear Jörg,

Apropos responsibility and the political: I remember the sentence “Be sand, not oil in the gears of the world” (Günter Eich). When you do something that disturbs processes, that doesn’t fit in smoothly. You can refer to it politically or spatially. “Sculpture is that which stands in the way”, Kaspar König once said, referring primarily to art in public space – which I find fitting, especially in relation to the Mann Monument. I don’t think a certain unwieldiness is a bad thing.

As far as responsibility in public art is concerned: there, themes and spaces are usually defined, one reacts to something. To participate in this, to get involved in something, is of course already a “political” decision. But then it’s a matter of balancing between guidelines, expectations and one’s own interests and ideas, one’s “responsibility”, if you will, towards oneself.

The fact that Elisabeth Mann-Borgese and Katia are also included in the memorial by means of street signs is already laid out in the invitation to tender, which is not only supposed to be about Thomas Mann, but about the family as a whole. Of course, the debates you mention are part of that. And in recent years there have been several streets named after women of the Mann family, such as Erika or Elisabeth. The family name ‘Mann’, on the other hand, paradoxically refers to the male gender alone. I also have a linguistic interest in names and their meaning.

Beyond the “real” signs, my contribution is to have a sign made for Katia, after whom no street is named anywhere. To have drawn attention to the little-noticed “Mrs Thomas Mann” was the merit of a friend who pointed me to Inge and Walter Jens’ biography Mrs Thomas Mann – the life of Katharina Pringsheim and to Viola Roggenkamp’s book on Erika Mann just as exchange and discussion are an integral part of the work on the memorial …